Click here and press the right key for the next slide.

(This may not work on mobile or ipad. You can try using chrome or firefox, but even that may fail. Sorry.)

also ...

Press the left key to go backwards (or swipe right)

Press n to toggle whether notes are shown (or add '?notes' to the url before the #)

Press m or double tap to slide thumbnails (menu)

Press ? at any time to show the keyboard shortcuts

What Are Preferences?

This book has ‘a philosophical end: elucidation of the notions of subjective probability and subjective desirability or utility’

(Jeffrey, 1983, p. xi)

‘we [...] view

subjective values and probabilities

as interrelated constructs of decision theory’

(Davidson, 1974, p. 146)

why necessary?

will get to that later

habitual process

Action occurs in the presence of Stimulus.

Outcome follows action

Agent is thereby rewarded

Stimulus-Action Link is strengthened due to reward

Given Stimulus, will Action occur? It depends on the strength of the Stimulus-Action Link.

‘goal-directed’ process

Action leads to Outcome.

Belief in Action-Outcome link is strengthened.

Agent has a Desire for the Outcome

Will Action occur? It depends on the Belief in the Action-Outcome Link and Agent’s Desire.

This book has ‘a philosophical end: elucidation of the notions of subjective probability and subjective desirability or utility’

(Jeffrey, 1983, p. xi)

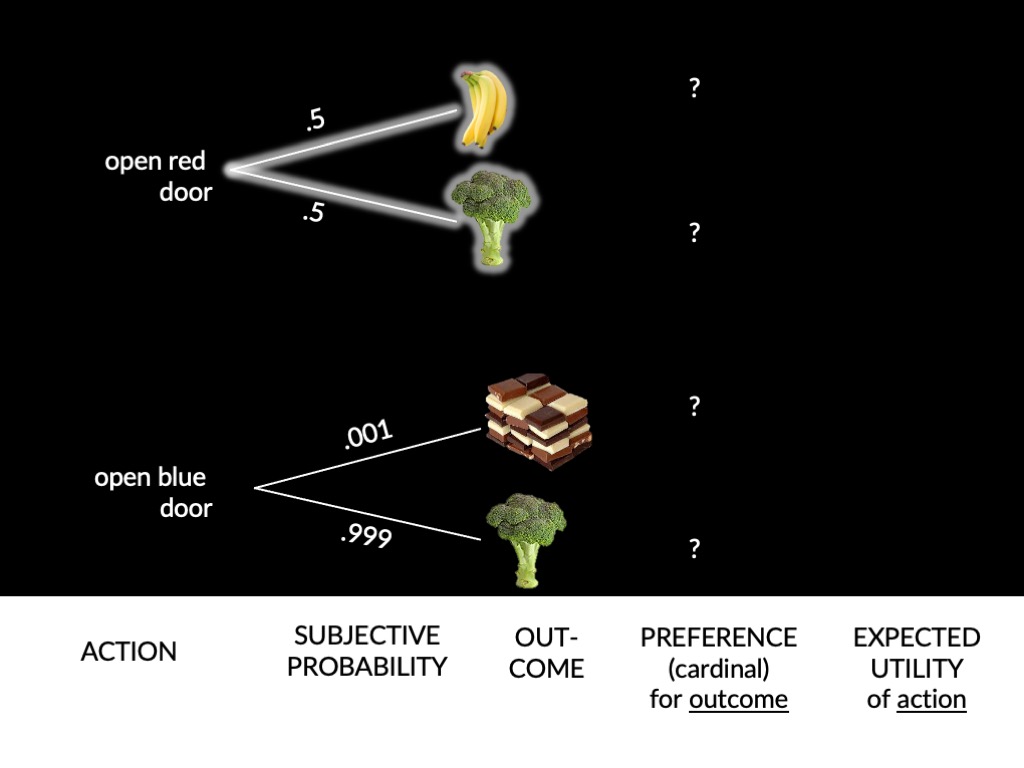

cannot infer preferences unless we know subjective probabilities

‘the revealed preference revolution of the 1930s (Samuelson, 1938)

... replaced the supposition that people are attempting to optimize any externally given criterion (e.g., some psychologically interpretable motion of utility, perhaps to be quantified in units of pleasure and pain).

Chater (2014)

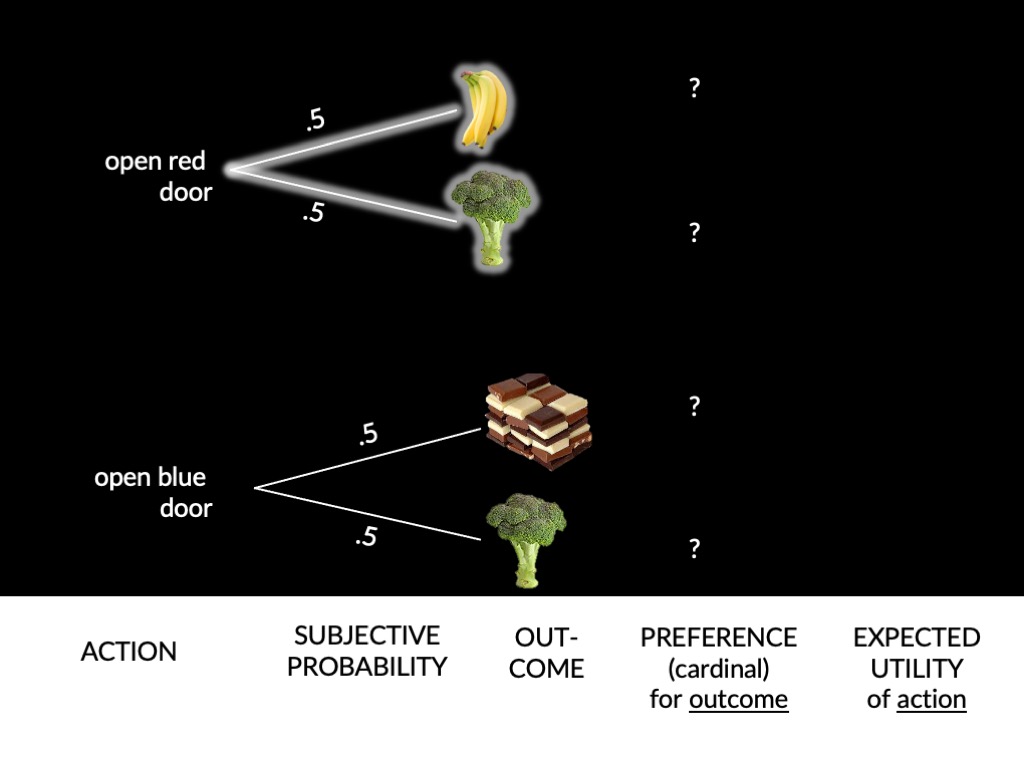

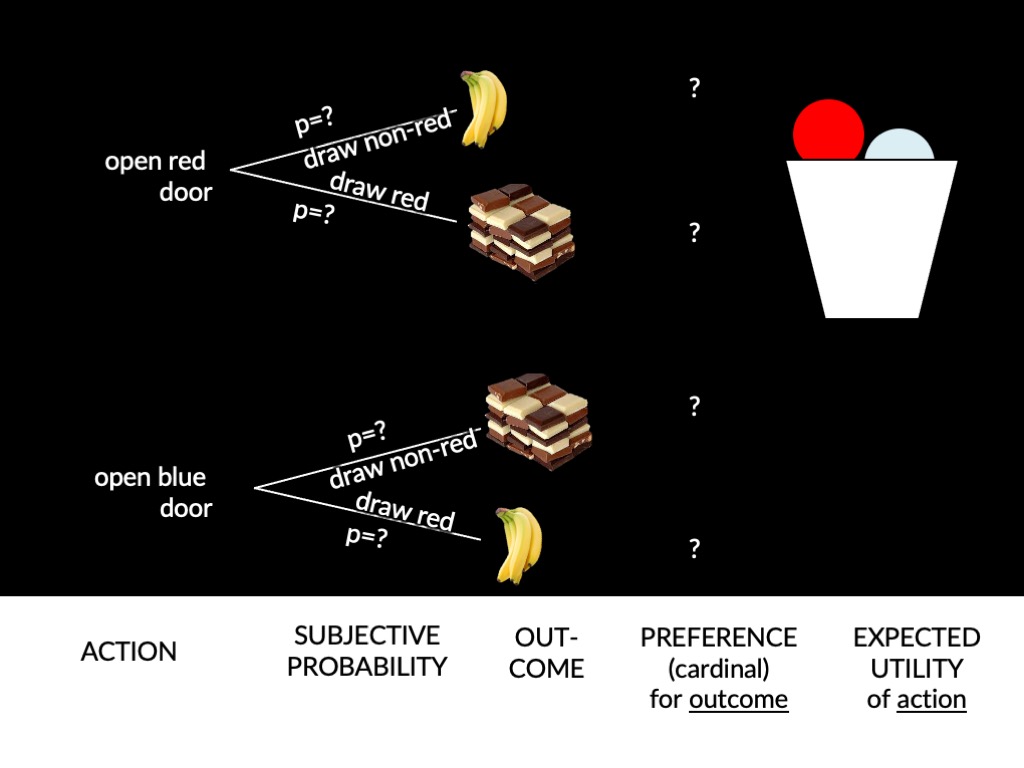

‘Suppose that A and B are consequences between which the agent is not indifferent, and that N is an ethically neutral condition [i.e. the agent is indifferent between N and not N].

Then N has probability 1/2 if and only if the agent is indifferent between the following two gambles:

1. B if N, A if not

2. A if N, B if not’

(Jeffrey, 1983, p. 47)

What have we done?

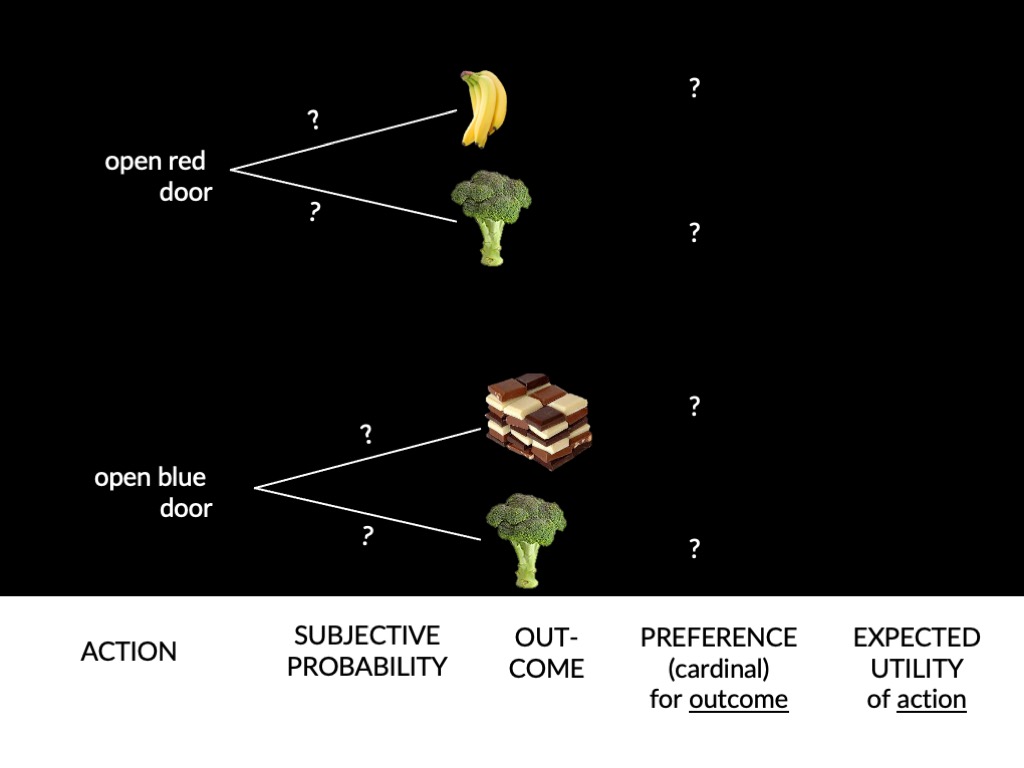

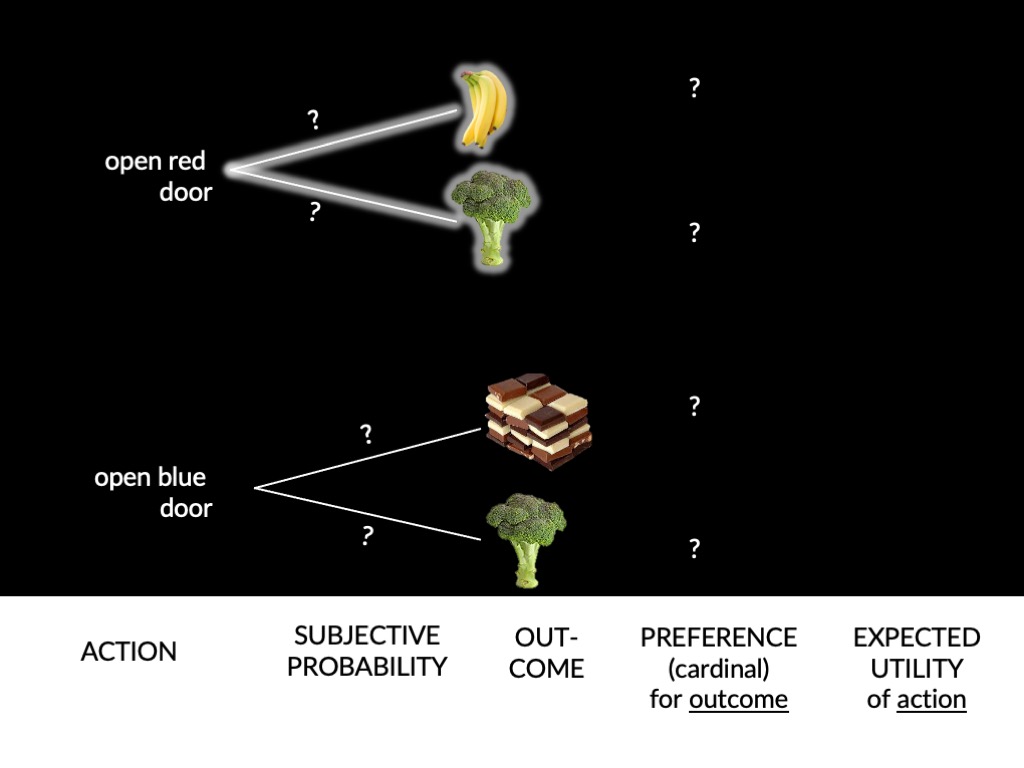

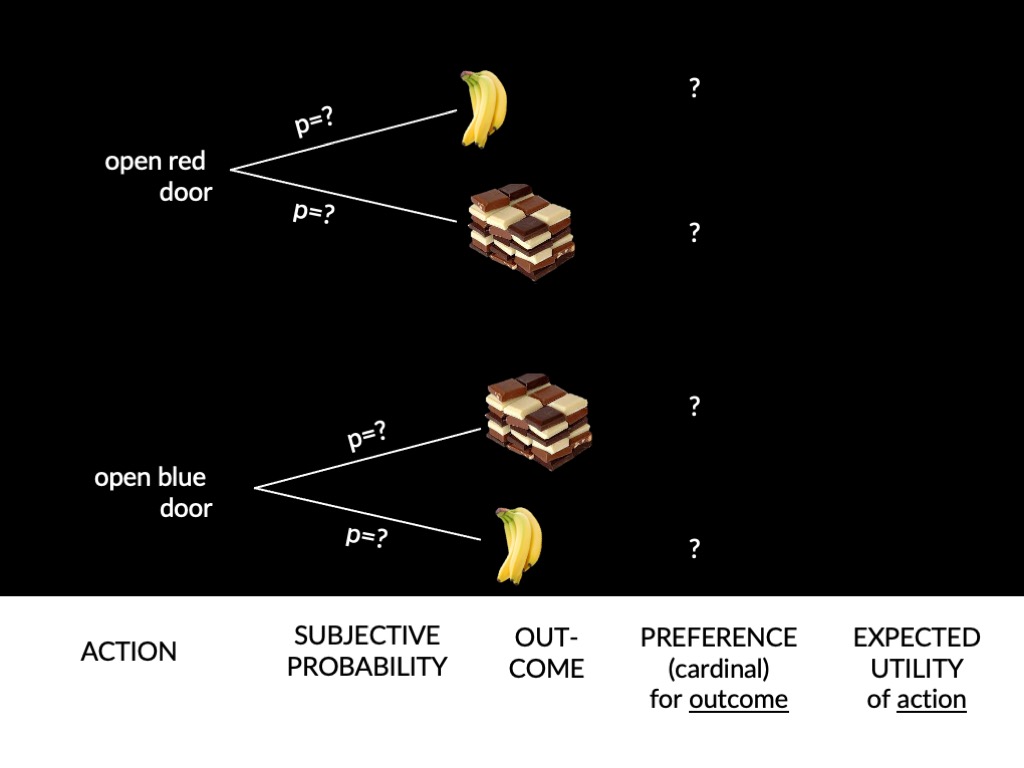

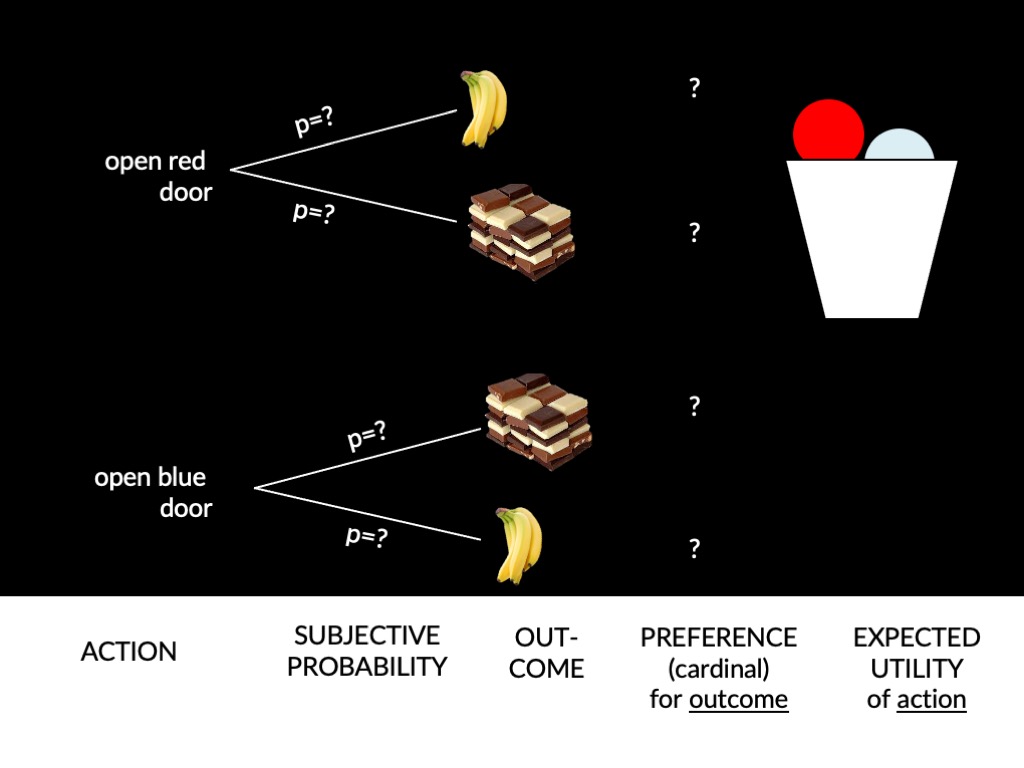

Your actions are a function of two things,

subjective probabilities

and preferences.

Ramsey’s method allows us to

infer both of these

from observations of the actions you perform

plus some background assumptions (axioms).

But what did we assume in characterising preferences?

transitivity

For any A, B, C ∈ S: if A⪯B and B⪯C then A⪯C.

completeness

For any A, B ∈ S: either A⪯B or B⪯A

continuity

‘Continuity implies that no outcome is so bad that you would not be willing to take some gamble that might result in you ending up with that outcome [...] provided that the chance of the bad outcome is small enough.’

independence

roughly, if you prefer A to B then you should prefer A and C to B and C.

Steele & Stefánsson (2020, p. §2.3)

things the theory

assumes

actions

outcomes

+ some axioms (background assumptions)

things the theory characterises

preference

subjective probability

rationality (?!)

This book has ‘a philosophical end: elucidation of the notions of subjective probability and subjective desirability or utility’

(Jeffrey, 1983, p. xi)

The axioms can be regarded as implicitly defining

preference

and

subjective probability.

why necessary?

1. We as researchers need a shared understanding of belief and desire.

2. There are three potential sources of shared understanding: folk psychology, philosophy and decision theory.

3. Folk psychology does not provide a shared understanding.

4. Nor does philosophy.

Therefore:

5. We need decision theory to provide a shared understanding.

Is

folk psychology

a source of common knowledge of principles

that implicitly define ‘intention’, ‘knowledge’, and the rest

?

Lewis (1972) vs Heider (1958)

As philosophers see

folk psychology ...

‘When someone is in so-and-so combination of mental states and receives sensory stimuli of so-and-so kind, he tends with so-and-so probability to be caused thereby to go into so-and-so mental states and produce so-and-so motor responses.’

(Lewis, 1972, p. 256)

(my|your|his|her|their) phone

is trying to (excluding ‘kill me’) [283,000]

wants to [278,000]

hates [147,000]

likes [86,800]

thinks (e.g. ‘My phone thinks I’m in another city’) [53,400]

is pretending [16,000]

Is

folk psychology

a source of common knowledge of principles

that implicitly define ‘intention’, ‘knowledge’, and the rest

?

Lewis (1972) vs Heider (1958)

further obstacle: diversity, inter- and intra-personal

1. We as researchers need a shared understanding of belief and desire.

2. There are three potential sources of shared understanding: folk psychology, philosophy and decision theory.

3. Folk psychology does not provide a shared understanding.

4. Nor does philosophy.

Therefore:

5. We need decision theory to provide a shared understanding.

| KNOWLEDGE | yes | no |

| Is it a mental state? | Williamson (2000) | Hyman (1999) |

| Knowing entails believing? | Rose & Schaffer (2013) | Radford (1966) |

| Is it a form of belief? | Sosa (2007) | Williamson (2000) |

| Valuable for action? | Plato’s Meno | Kaplan (1985) |

| Is humanly attainable? | [others] | Unger (1975) |

| Depends on context? | Lewis (1996) | [lots] |

Which things manifest agency?

‘The paramecium’s swimming through the beating of its cilia, in a coordinated way, and perhaps its initial reversal of direction, count as agency.’

(Burge, 2009, p. 259)

‘the paramecium cannot be an agent [...]

None of its interactions with the environment [...] need involve anything like an act on the part of the paramecium.’

(Steward, 2009, p. 227)

Do these two have a shared understanding of agency?

Philosophical Folk Psychology

another obstacle ...

‘epistemic case intuitions are generated by [...] folk psychology’

Nagel (2012, p. 510)

‘some part of us finds it almost impossible not to categorise them as’ agents

Steward (2009, p. 229)

1. We as researchers need a shared understanding of belief and desire.

2. There are three potential sources of shared understanding: folk psychology, philosophy and decision theory.

3. Folk psychology does not provide a shared understanding.

4. Nor does philosophy.

Therefore:

5. We need decision theory to provide a shared understanding.

This book has ‘a philosophical end: elucidation of the notions of subjective probability and subjective desirability or utility’

(Jeffrey, 1983, p. xi)

‘we should think of

meanings and beliefs

as interrelated constructs of a single theory

just as we already view

subjective values and probabilities

as interrelated constructs of decision theory’

(Davidson, 1974, p. 146)

why necessary?

for shared understanding!

so far ...

1. We understand what decision theory is;

2. ... and how it can be used to provide us as researchers with a shared understanding of belief and desire.

3. This is necessary because neither folk psychology nor philosophy provide a shared understanding.