Click here and press the right key for the next slide.

(This may not work on mobile or ipad. You can try using chrome or firefox, but even that may fail. Sorry.)

also ...

Press the left key to go backwards (or swipe right)

Press n to toggle whether notes are shown (or add '?notes' to the url before the #)

Press m or double tap to slide thumbnails (menu)

Press ? at any time to show the keyboard shortcuts

Philosophical Theories of Action

challenge

Discover why people act,

individually and jointly.

What distinguishes your actions from things that merely happen to you? (‘The Problem of Action’)

- kinematic features?

- desired outcomes?

- coordination of body parts?

action

mere happening

intended fall

accidental fall

comparable kinematics

skillful execution

lucky accident

comparable outcomes

toddler walking

infant walking reflex

comparable coordination

What distinguishes your actions from things that merely happen to you? (‘The Problem of Action’)

- kinematic features?

- desired outcomes?

- coordination of body parts?

- intention

Standard Answer: actions are those events which stand in an appropriate causal relation to an intention.

action

mere happening

intended fall

accidental fall

comparable kinematics

skillful execution

lucky accident

comparable outcomes

toddler walking

infant walking reflex

comparable coordination

What distinguishes your actions from things that merely happen to you? (‘The Problem of Action’)

- kinematic features?

- desired outcomes?

- coordination of body parts?

- intention

Standard Answer: actions are those events which stand in an appropriate causal relation to an intention.

Causal Theory of Action: an event is action ‘just in case it has a certain sort of psychological cause’ (Bach, 1978, p. 361).

challenge

Discover why people act,

individually and jointly.

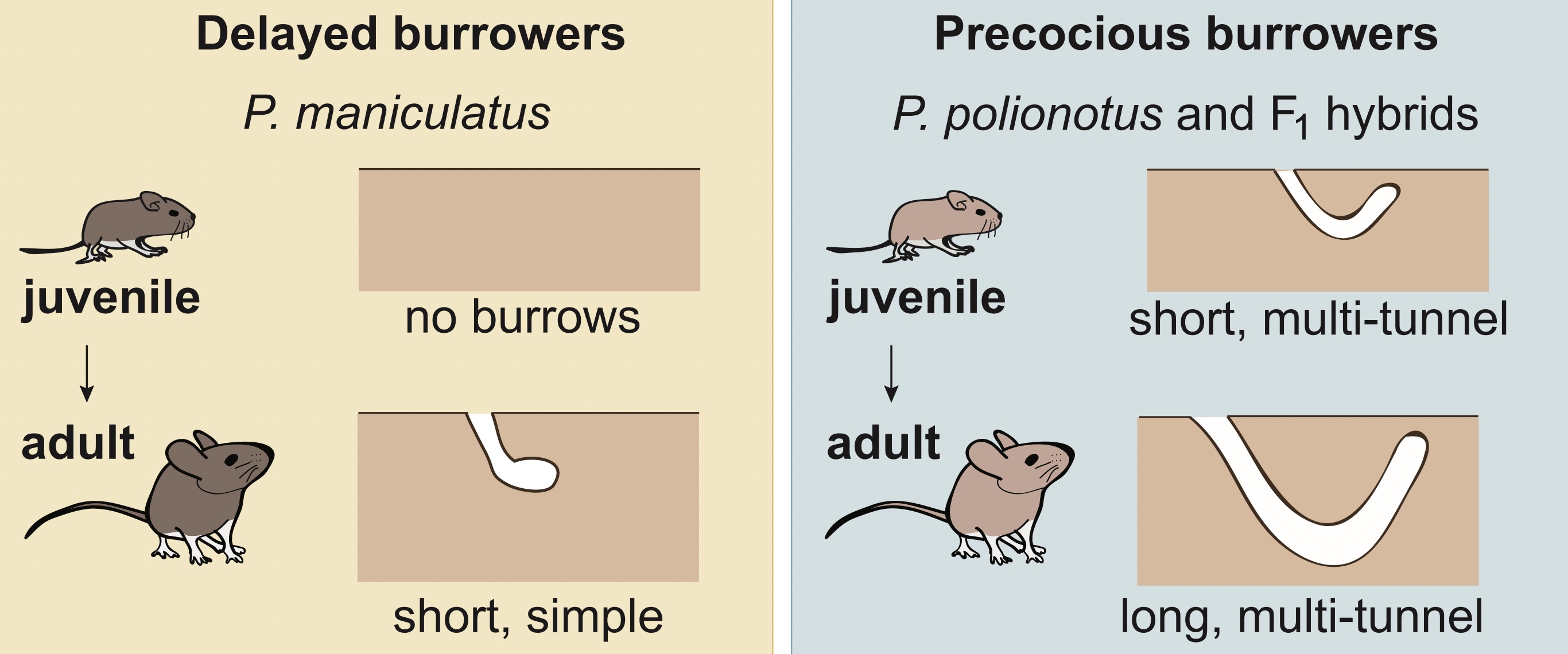

complication: ‘reflex’ behaviours

action

mere happening

intended fall

accidental fall

comparable kinematics

skillful execution

lucky accident

comparable outcomes

toddler walking

infant walking reflex

comparable coordination

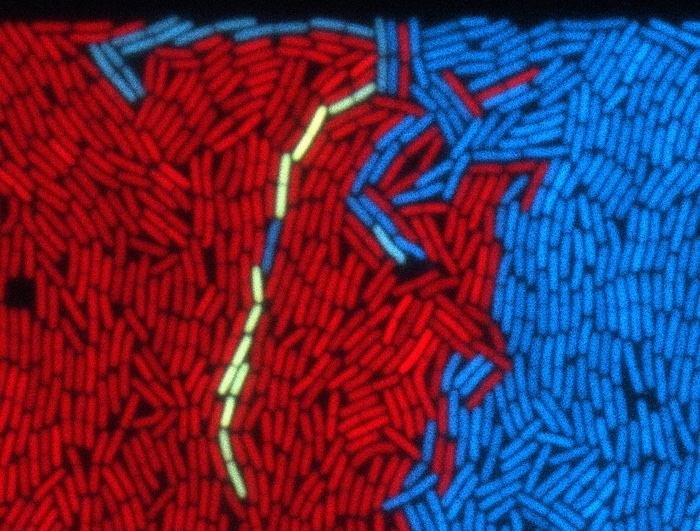

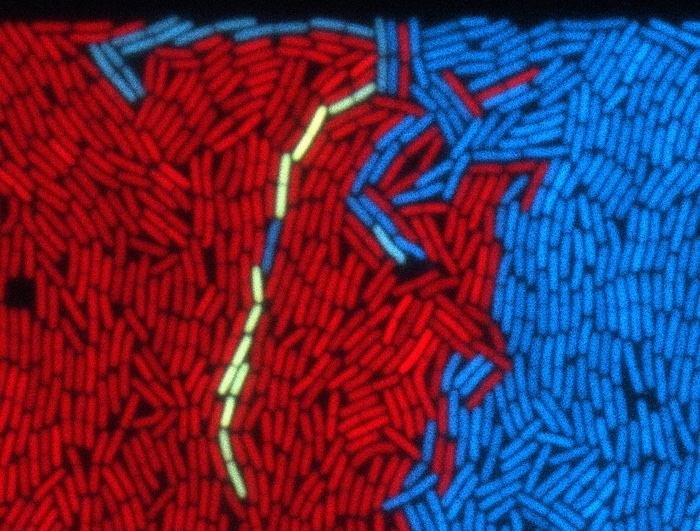

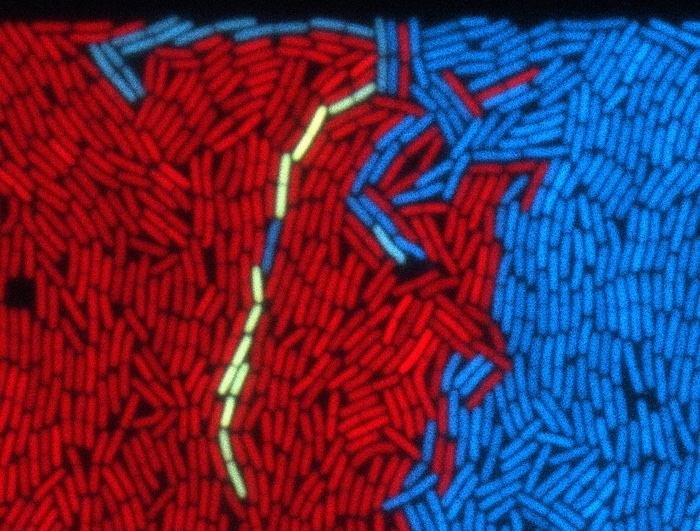

Metz, Bedford, Pan, & Hoekstra (2017, p. graphical abstract, part)

What distinguishes your actions from things that merely happen to you? (‘The Problem of Action’)

- kinematic features?

- desired outcomes?

- coordination of body parts?

- intention

Standard Answer: actions are those events which stand in an appropriate causal relation to an intention.

Causal Theory of Action: an event is action ‘just in case it has a certain sort of psychological cause’ (Bach, 1978, p. 361).

action

mere happening

intended fall

accidental fall

comparable kinematics

skillful execution

lucky accident

comparable outcomes

toddler walking

infant walking reflex

comparable coordination

challenge

Discover why people act,

individually and jointly.