Click here and press the right key for the next slide.

(This may not work on mobile or ipad. You can try using chrome or firefox, but even that may fail. Sorry.)

also ...

Press the left key to go backwards (or swipe right)

Press n to toggle whether notes are shown (or add '?notes' to the url before the #)

Press m or double tap to slide thumbnails (menu)

Press ? at any time to show the keyboard shortcuts

Conclusion to Philosophical Issues in Behavioural Science

conclusion

To understand why people act, individually and jointly.

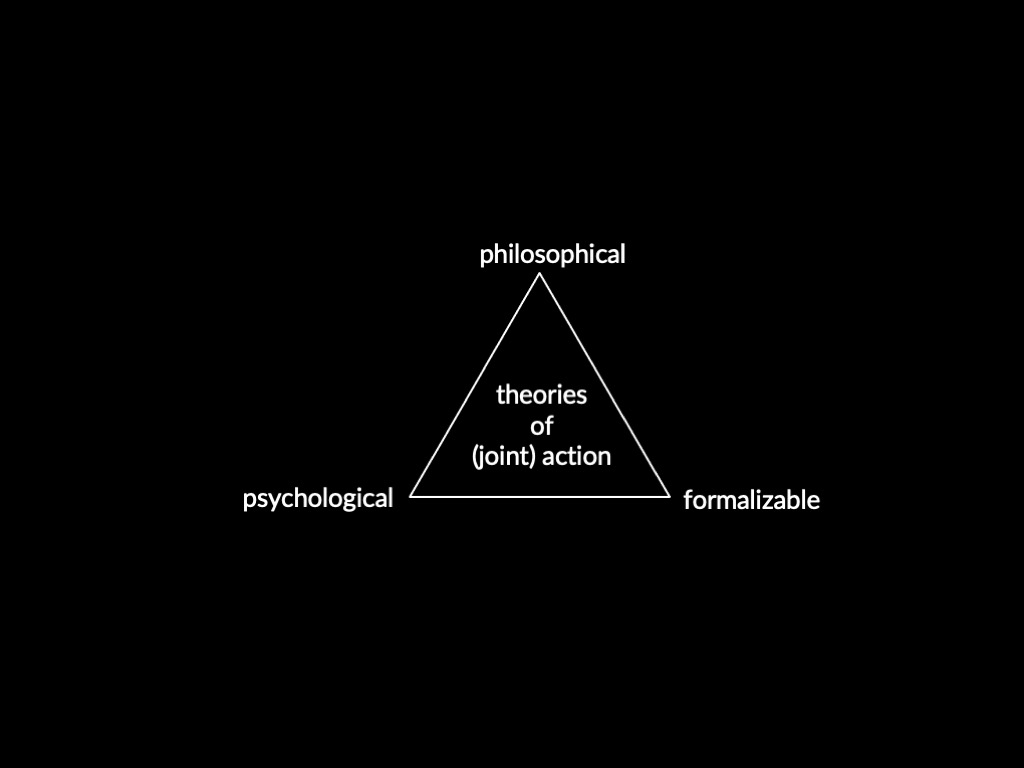

Philosophical, psychological and formal answers are—or appear—both mutually dependent and inconsistent.

This is an obstacle to full understanding,

but one that you can overcome.

slower conclusion

challenge

Discover why people act,

individually and jointly.

When you act,

there are reasons why you act;

you know the reasons;

you act because you know the reasons; and

the reasons justify your action. make your action intelligible.

How can we turn this into a theory? Is it true?

relevance to essay questions

Integration Questions

Identify theories from two or more disciplines

(philosophical, psychological or formal)

which appear to target a single set of phenomena

while saying incompatible things about it ...

1. Are they actually inconsistent? ✔?

2. If so: how, if at all, should either or both theories be refined?

Standard Solution to The Problem of Action vs the dual-process theory of instrumental action

Standard Solution to The Problem of Action vs theories of motor control

Decision Theory vs the dual-process theory of instrumental action

Bratman’s theory of shared intention vs team reasoning

Bratman’s theory of shared intention vs motor representations of collective goals

philosophy

What distinguishes actions from things that merely happen to you?

psychology

Which processes are involved in selecting the goals of actions?

Actions are those events which are appropriately related to intentions.

At least two: habitual and goal-directed.

apparent inconsistency

Nothing to say about processes.

Nothing to say about what action is.

apparent mutual dependence

1. Preferences shape intention:

pathological cases aside,

if there are two outcomes

and you prefer one outcome to the other,

and there are no reasons to pursue the other outcome,

then you will not intend an action that brings about the less preferred action.

2. Where habitual processes dominate, you sometimes pursue less preferred outcomes.

Therefore

3. Not everything you do involves intention.

philosophy

What distinguishes actions from things that merely happen to you?

psychology

Which processes are involved in selecting the goals of actions?

Actions are those events which are appropriately related to intentions.

At least two: habitual and goal-directed.

apparent inconsistency

Nothing to say about processes.

Nothing to say about what action is.

apparent mutual dependence

Integration Questions

Identify theories from two or more disciplines

(philosophical, psychological or formal)

which appear to target a single set of phenomena

while saying incompatible things about it ...

1. Are they actually inconsistent? ✔?

2. If so: how, if at all, should either or both theories be refined?

Integration Questions for Joint Action

philosophy

What distinguishes joint actions from things we do in parallel but merely individually?

economics

How can we model rational behaviour in social interactions?

shared intention

game theory team reasoning

Pacherie’s Reconciliation:

‘shared intention lite’

nothing to say about agents without planning abilities

no role for planning abilities

apparent mutual dependence

Integration Questions

Identify theories from two or more disciplines

(philosophical, psychological or formal)

which appear to target a single set of phenomena

while saying incompatible things about it ...

1. Are they actually inconsistent? ✔?

2. If so: how, if at all, should either or both theories be refined?

challenge

Discover why people act,

individually and jointly.

basic theories and discoveries

from three disciplines needed

to answer the question

to reach beyond

you need to look beyond

🔑

inconsistencies abound (maybe)

but integration is possible (definitely)