Click here and press the right key for the next slide.

(This may not work on mobile or ipad. You can try using chrome or firefox, but even that may fail. Sorry.)

also ...

Press the left key to go backwards (or swipe right)

Press n to toggle whether notes are shown (or add '?notes' to the url before the #)

Press m or double tap to slide thumbnails (menu)

Press ? at any time to show the keyboard shortcuts

Motor Representations Aren’t Intentions

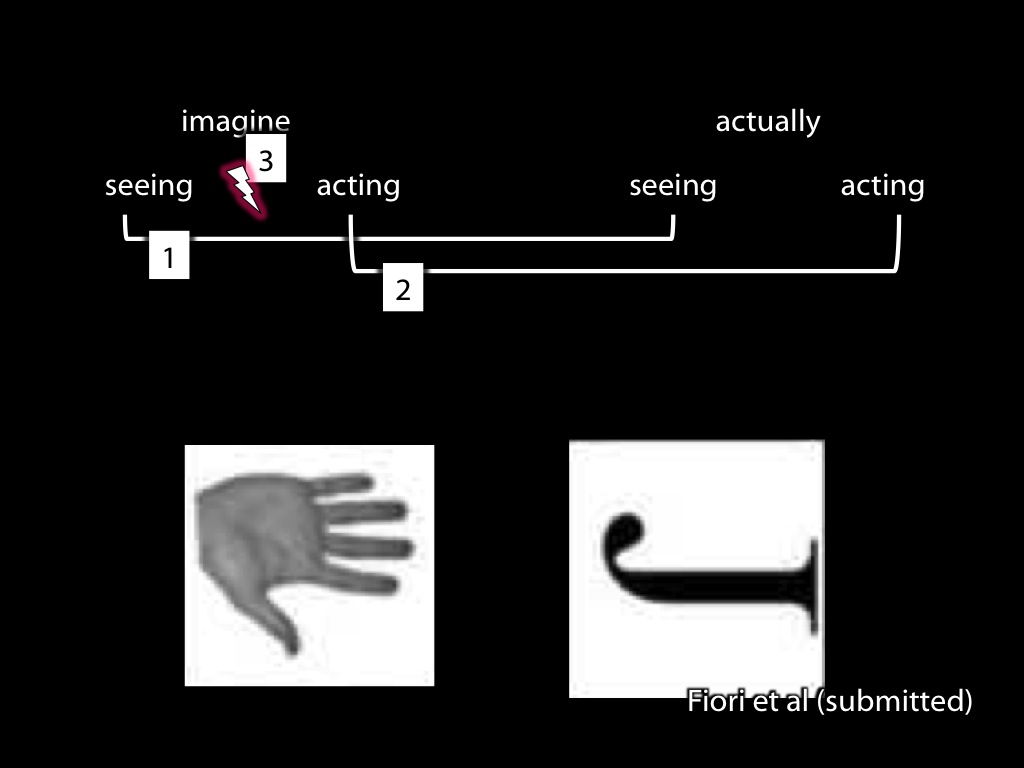

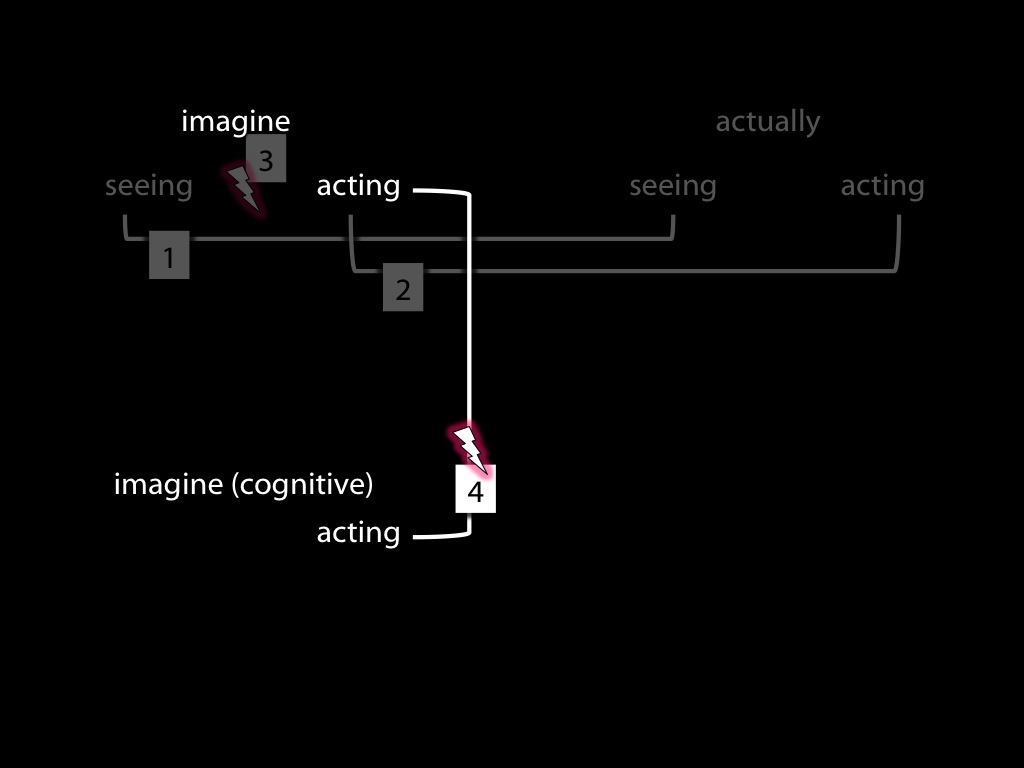

Fiori et al. (2013)

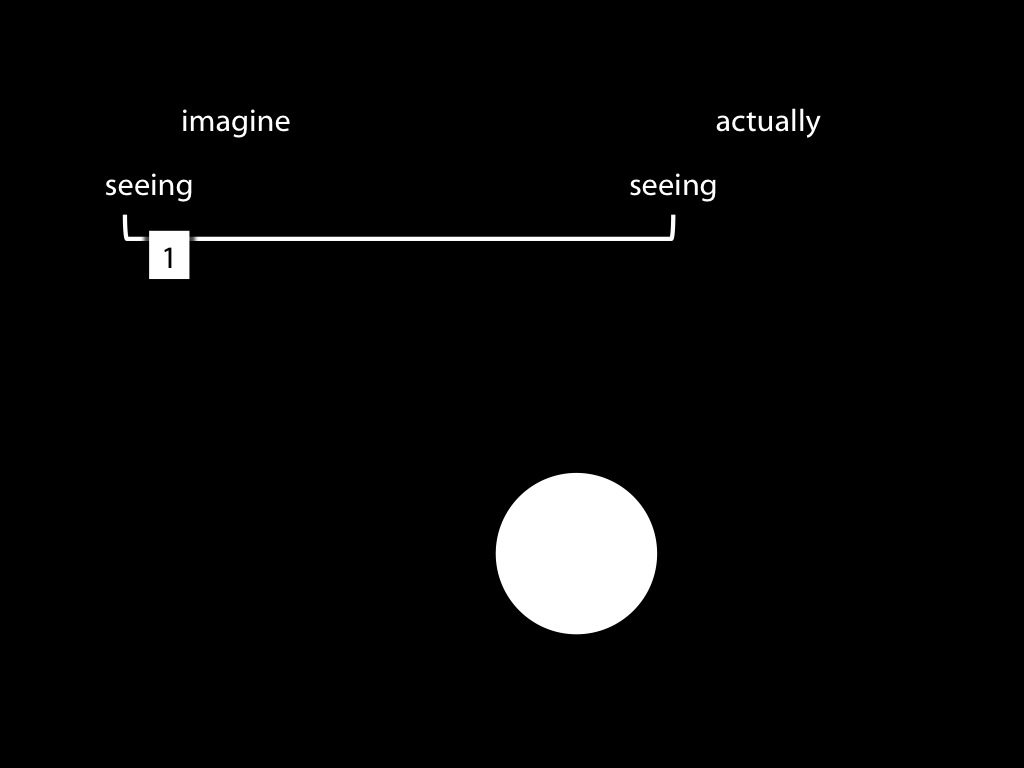

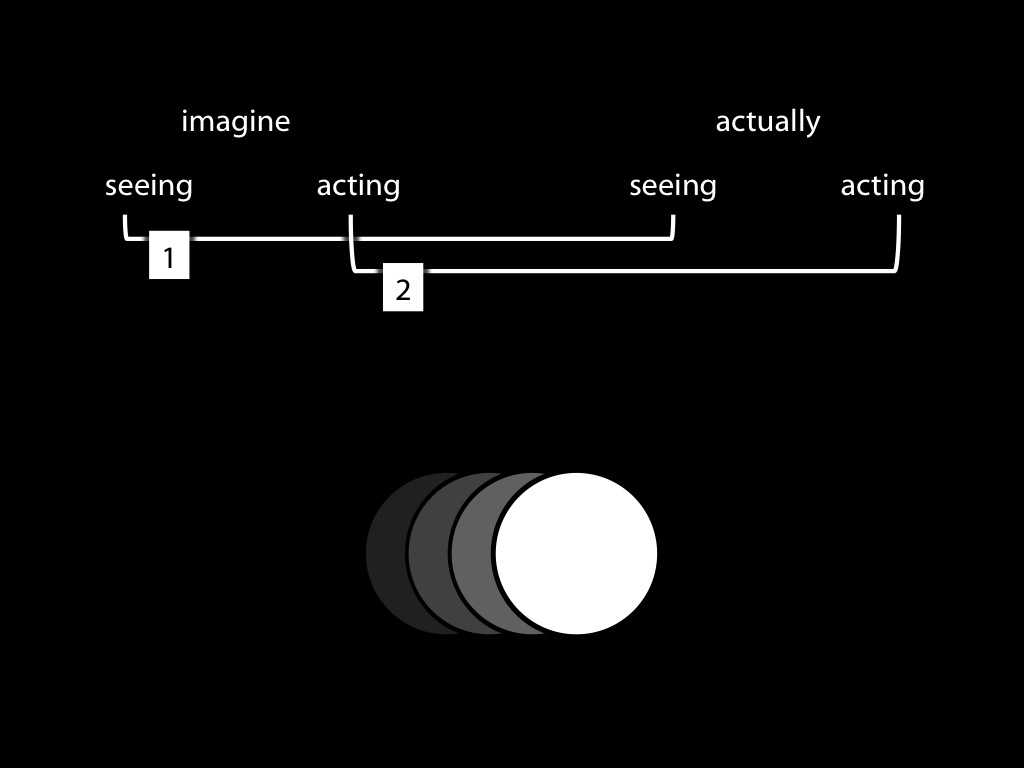

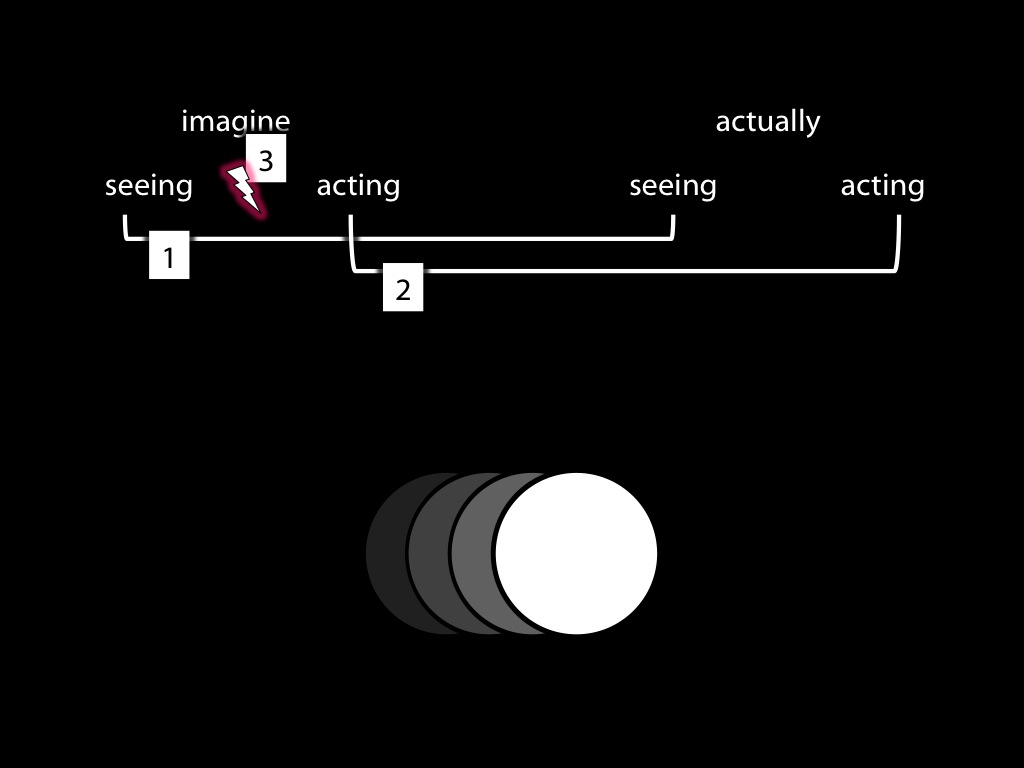

Only representations with a common format can be inferentially integrated.

Any two intentions can be inferentially integrated in practical reasoning.

My intention that I visit the ZiF is a propositional attitude.

Therefore:

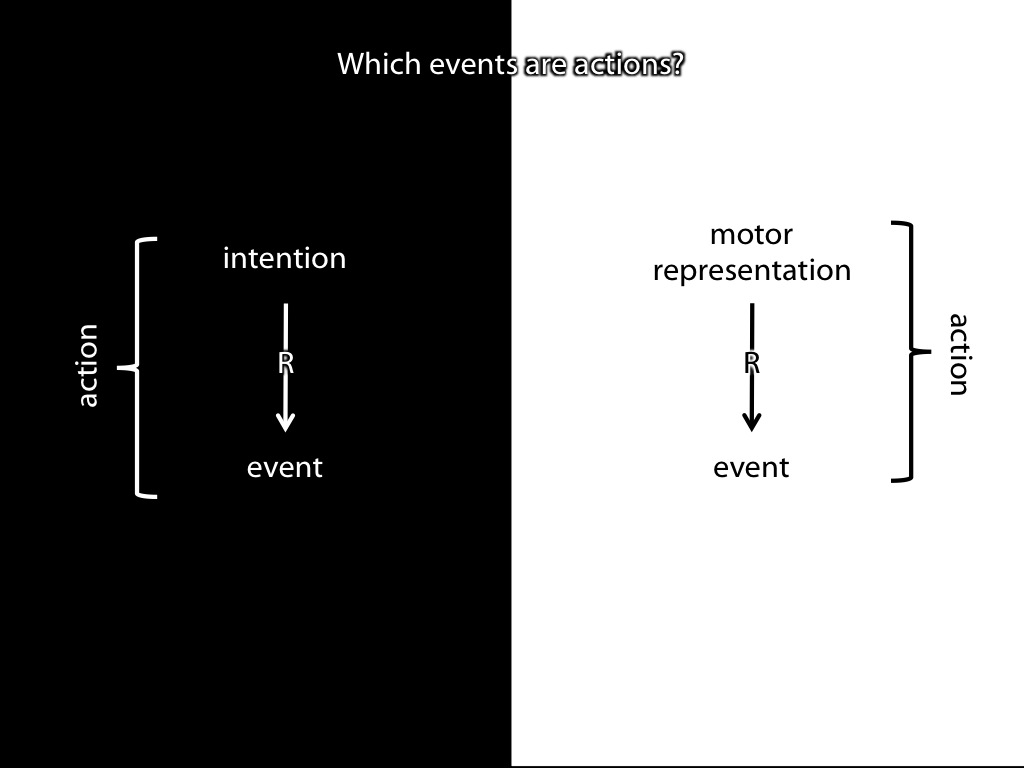

No motor representations are propositional attitudes.

All intentions are propositional attitudes

No motor representations are intentions.

intention = motor representation? No!

essay questions related to todays lecture

How, if at all, should a philosophical theory of action incorporate scientific discoveries about the control of action?

Could some motor representations be intentions?

Which psychological structures enable agents to coordinate their plans? What if anything do these mechanisms reveal about how acting together differs from acting in parallel but merely individually?

How, if at all, should a philosophical theory of acting together incorporate scientific discoveries about the interpersonal coordination of action?

plan

1. What is the relation between a very small scale instrumental action and the outcome or outcomes to which it is directed? ✓

2. How, if at all, does answering this question challenge the Standard Answer to the Problem of Action? ✓

3. Is there a parallel set of issues concerning joint action? ✓