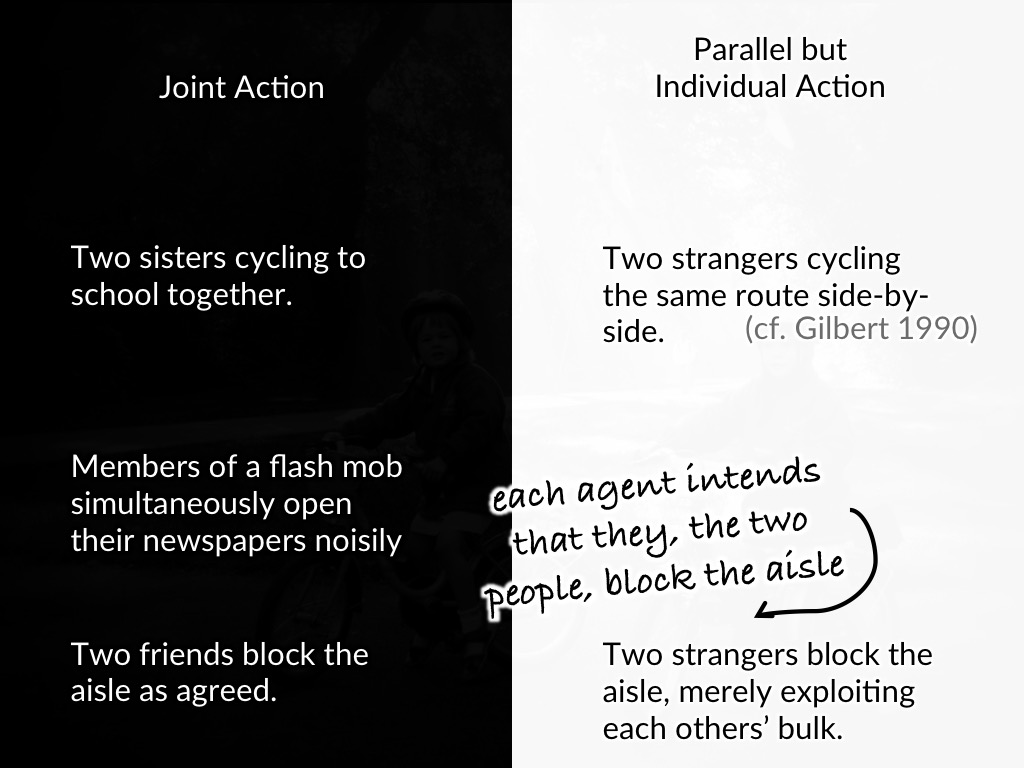

another contrast case: blocking the aisle

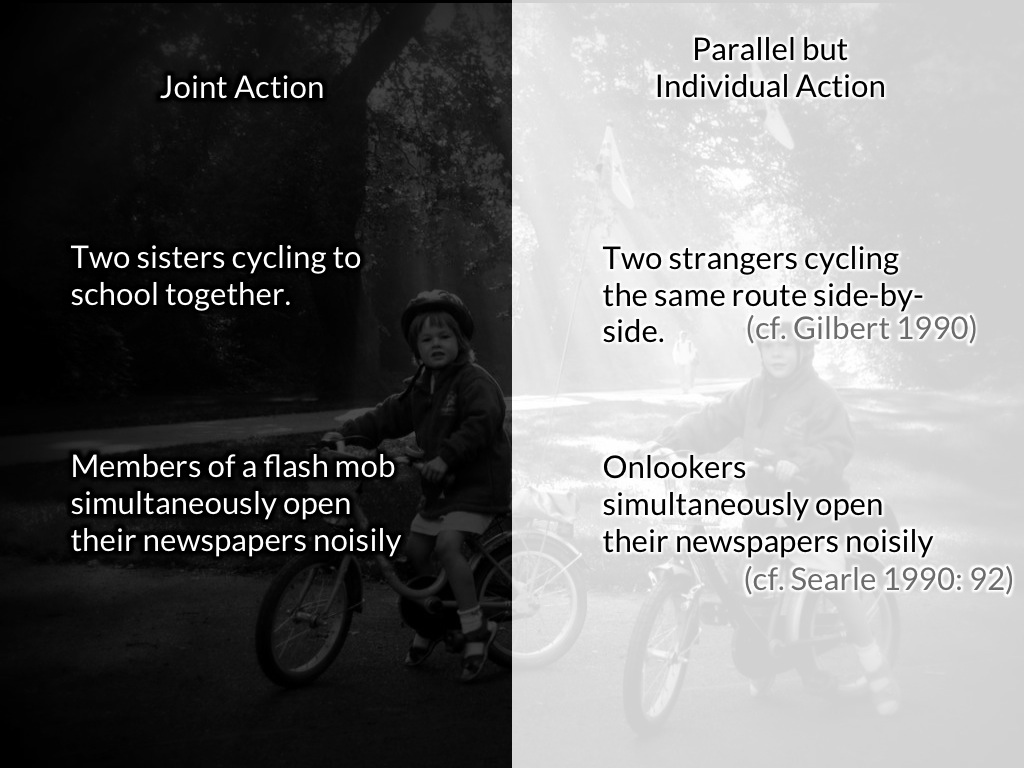

Imagine two sisters who, getting off an aeroplane, tacitly agree to exact revenge on

the unruly mob of drunken hens behind them by standing so as to block the aisle together.

This is a joint action.

Meanwhile on another flight, two strangers happen to be so configured that they are

collectively blocking the aisle.

The first passenger correctly anticipates that the other passenger, who is a

complete stranger, will not be moving from her current position for some time.

This creates an opportunity for the first passenger: she intends that they,

she and the stranger, block the aisle.

And, as it happens, the second passenger’s thoughts mirror the first’s.

[transcript from ug version]

I'm trying to construct two cases, one in

which there's genuine joint action and two people are blocking

the aisle, and one in which there's clearly parallel but

merely individual action

and two people are blocking the aisle.

So contrast cases are similar as possible, except for the

one is clearly joint action and one is clearly not.

So here's the joint action case.

You and I are on a plane together and

there's a party.

There's like a stag party.

And they've been really, really noisy and kept us awake

overnight on this flight.

And we kind of, you know, we're not best pleased

about this.

And then it turns out that they're really antsy because

our plane is a little bit delayed and they've got

a tight connection.

Now, you and I are not normally this evil, but

we have been sleep deprived on a transatlantic flight by

some particularly obnoxious stag party.

And so our normal good nature has failed us.

And so Naran says to me, Steve, why don't we

just stand in the aisle for a good long while

and I'm going to spend some time pulling out this

heavy case or faking it, and you're going to be

down there sort of trying to lift up the bag,

and we'll block the aisle and we'll just, you know,

we won't make them miss their flight, but we're going

to make them, like, really a bit nervous about this

whole thing.

And, you know, I'm like, Naren, that's a great idea.

You know, we're going to get our revenge on them.

And so we do that.

We're performing a joint action.

And the joint action is blocking the aisle with the

aim of preventing the stag party from exiting the plane

in a timely fashion, and so repaying them for the

night of sleep that we lost.

This is clearly a

paradigm example of joint action.

I'm not proud of what we did now, but it's

a paradigm example of joint action.

There's another occasion in my parallel world where it's

not going to be a joint action parallel, but merely

individual.

So there are two people, say it's Chris and

Mina.

They don't know each other.

They're complete strangers to each other.

And what happens is that Mina observes Chris attempting or

apparently attempting to pull down his heavy suitcase, and Mina

thinks to herself, Chris is going to be there for

a good long time.

I will block the stag party behind me by bending

down and pretending to lift up this heavy case, using

Chris merely as a kind of like space filling device.

So I think he's going to be there for a

while so I can block their exit by holding on

and pretending this case.

What Mina does not realise is that Chris has observed

her bag, and he thought, mistakenly, that Mina's bag was

really properly wedged in there, and he, with the intention

that he and Mina would lock the aisle, has decided

to spend a long time pretending to get his heavy

bag down.

So Chris intended that he, he and Mina blocked the

aisle together, thinking from Chris's point of view that Mina

was simply going to be there for a while.

And so from his point of view, she simply space

occupying.

Mina intends that she, Chris and Mina block the aisle

together, but from her point of view, Chris just happens

to be someone who is bit incompetent and can't get

his bag down.

So they both meet the conditions of the simple theory,

but they have no awareness of each other.

Mina.

They have no awareness of each other.

And so it looks like they're acting in parallel, but

merely individually.

And indeed, if you ask them, if you said, Chris,

you know, are you doing this with Mina?

Chris would say, well, kind of, because I'm relying on

her, but it's not.

I'm not really doing it with her.

I don't know her at all.

We've never spoken about this.

I think she just can't get her bag out.

And, Mina, you would say the same about Chris.

There is a contrast.

One of these cases is joint action.

One of them is parallel but merely individual.

And yet the conditions of the simple theory are met

in both cases.

And therefore this is a counterexample to the claim that

the simple theory allows us to solve the problem of

joint action, to say what distinguishes joint actions from parallel,

but merely individual actions.

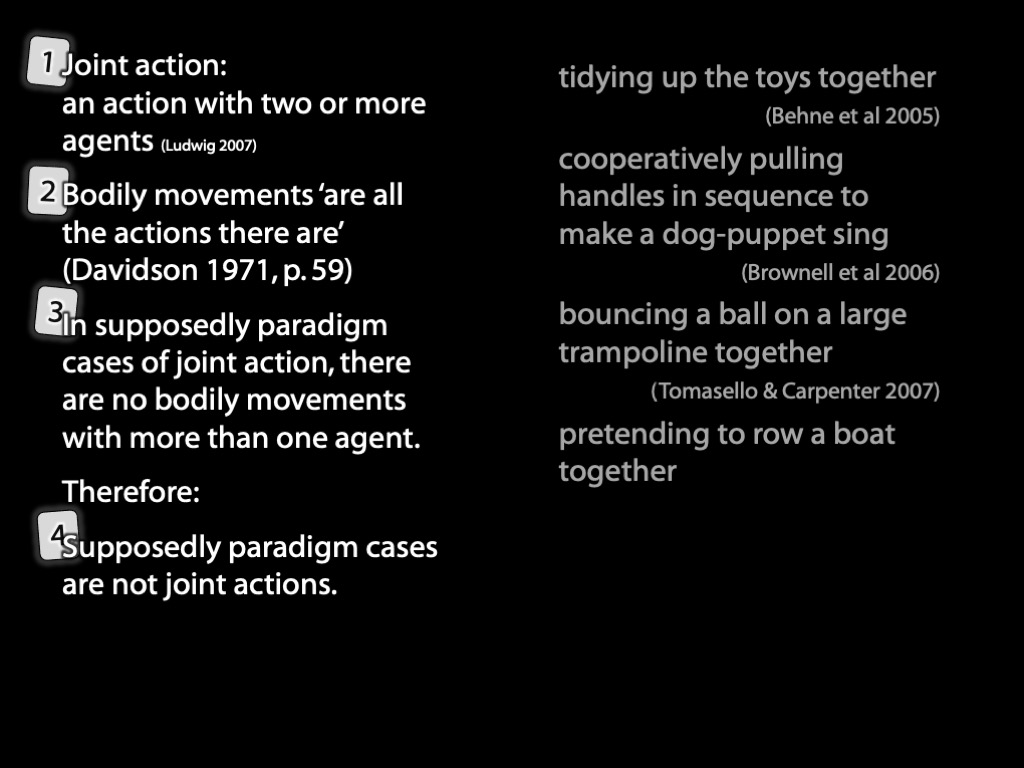

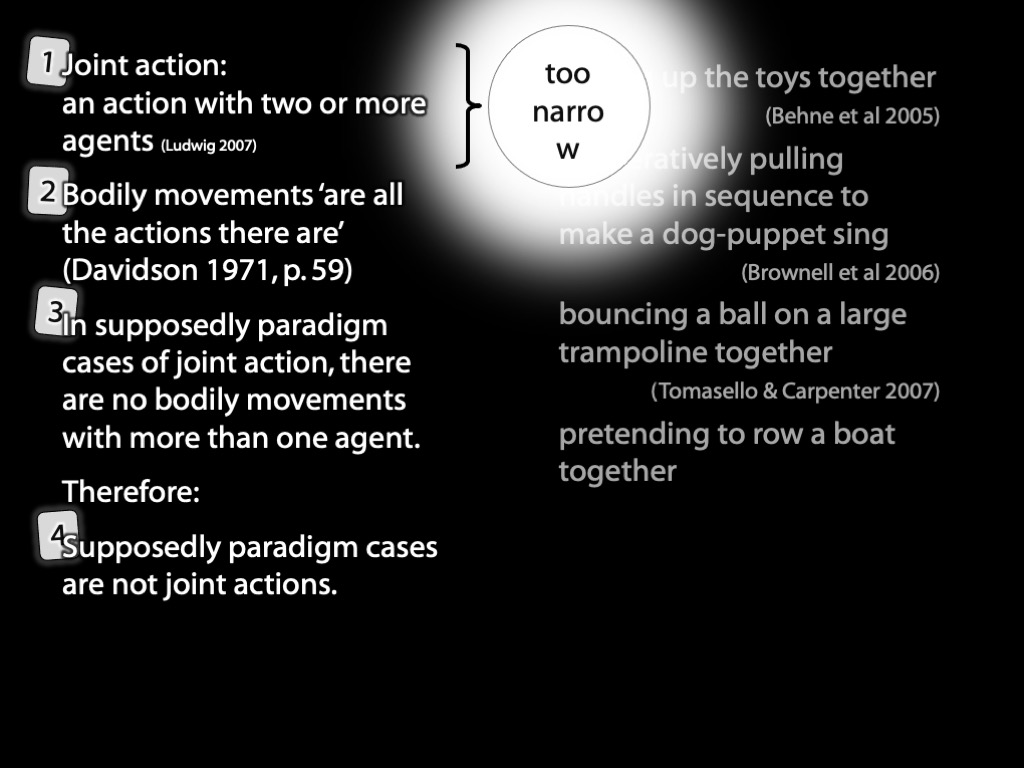

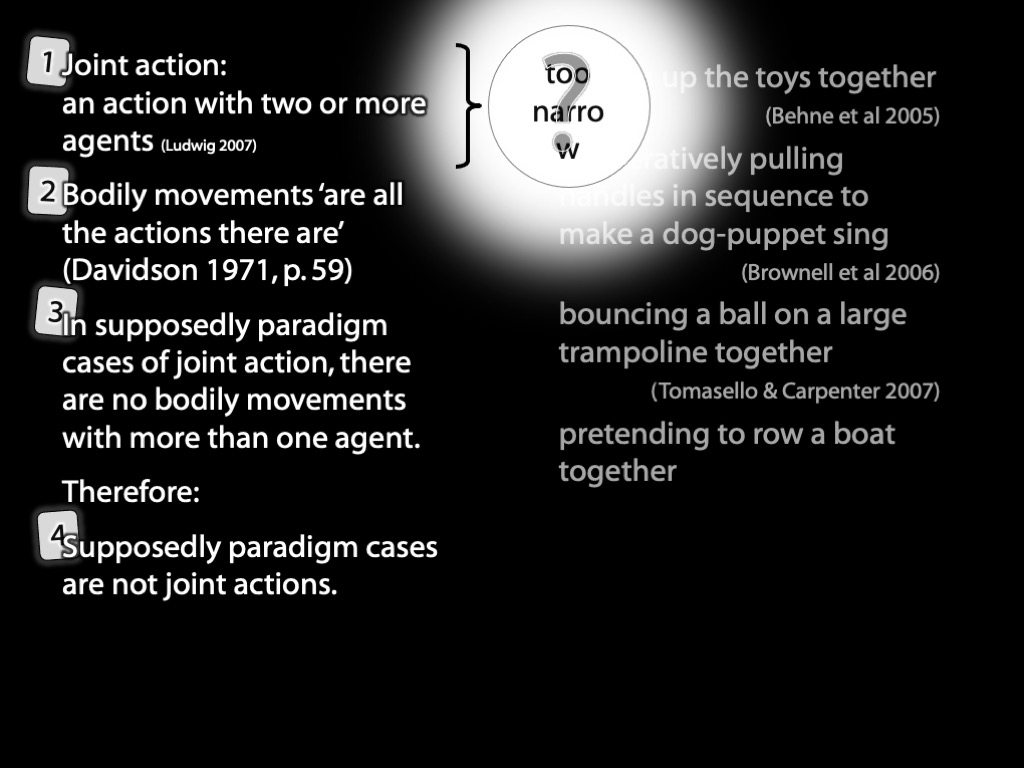

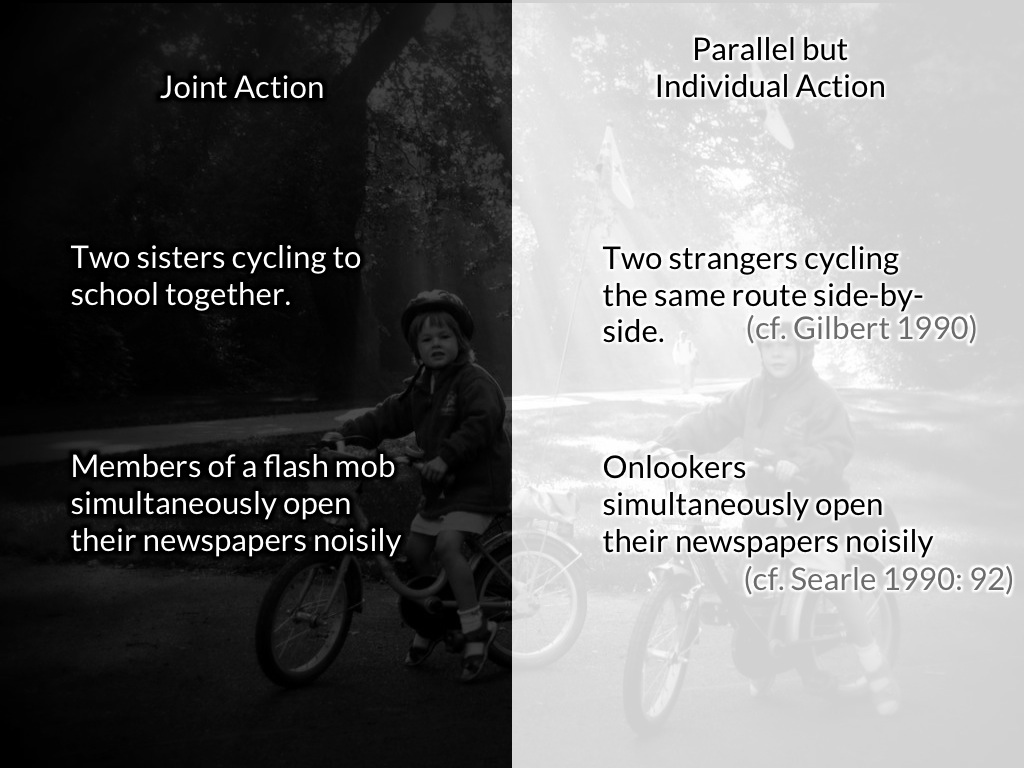

1. The sisters perform an intentional joint action; the strangers’ actions are parallel but merely individual.

2. In both cases, the conditions of the Simple Theory are met.

The feature under consideration as distinctive of joint action is present:

each passenger is acting on her intention that they, the two passengers, block the aisle.

therefore:

3. The Simple Theory does not correctly answer the question, What distinguishes joint actions from parallel but merely individual actions?

Is it really a counterexample?