Click here and press the right key for the next slide.

(This may not work on mobile or ipad. You can try using chrome or firefox, but even that may fail. Sorry.)

also ...

Press the left key to go backwards (or swipe right)

Press n to toggle whether notes are shown (or add '?notes' to the url before the #)

Press m or double tap to slide thumbnails (menu)

Press ? at any time to show the keyboard shortcuts

Objections to the Simple Theory of Joint Action

The Simple Theory

Two or more agents perform an intentional joint action

exactly when there is an act-type, φ, such that

each agent intends that

they, these agents, φ together

and their intentions are appropriately related to their actions.

Bratman’s ‘mafia case’

1. I intend that we, you and I, go to NYC together.

2. You intend that we, you and I, go to NYC together.

3. You intend that we, you and I, go to NYC together by way of you forcing me into the back of my car.

Walking together in the Tarantino sense

1. I intend that we, you and I, walk together.

... by means of my forcing you at gun point.

2. You intend that we, you and I, walk together.

... by means of you forcing me at gun point.

the threat of collapse: trading intuitions

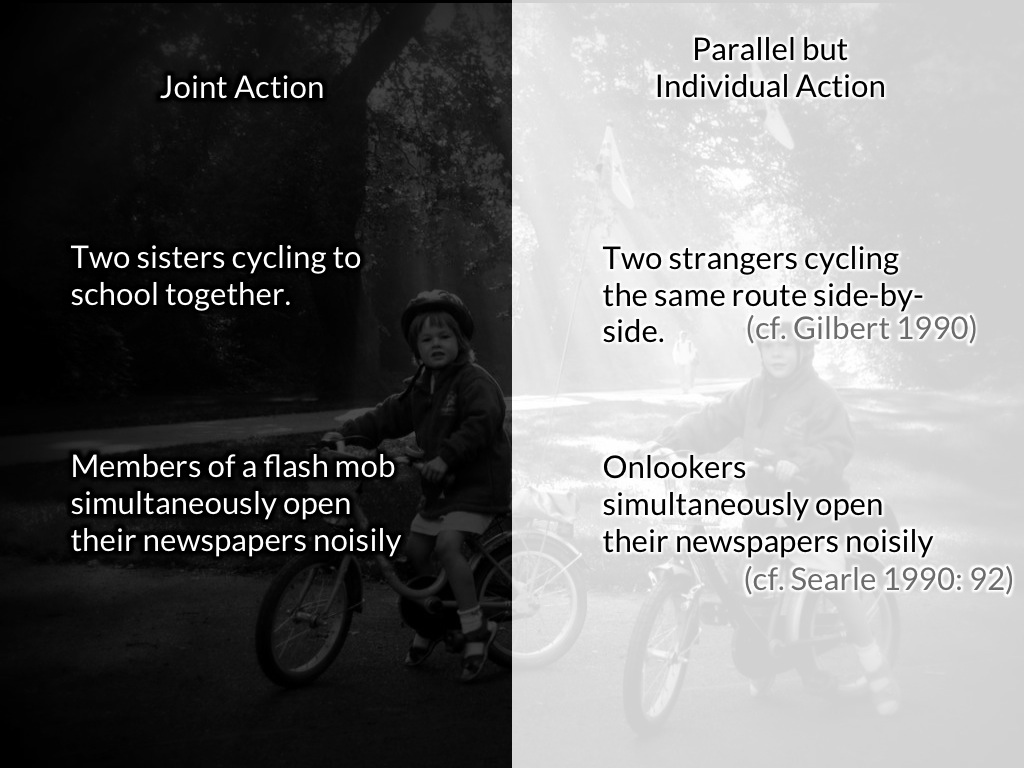

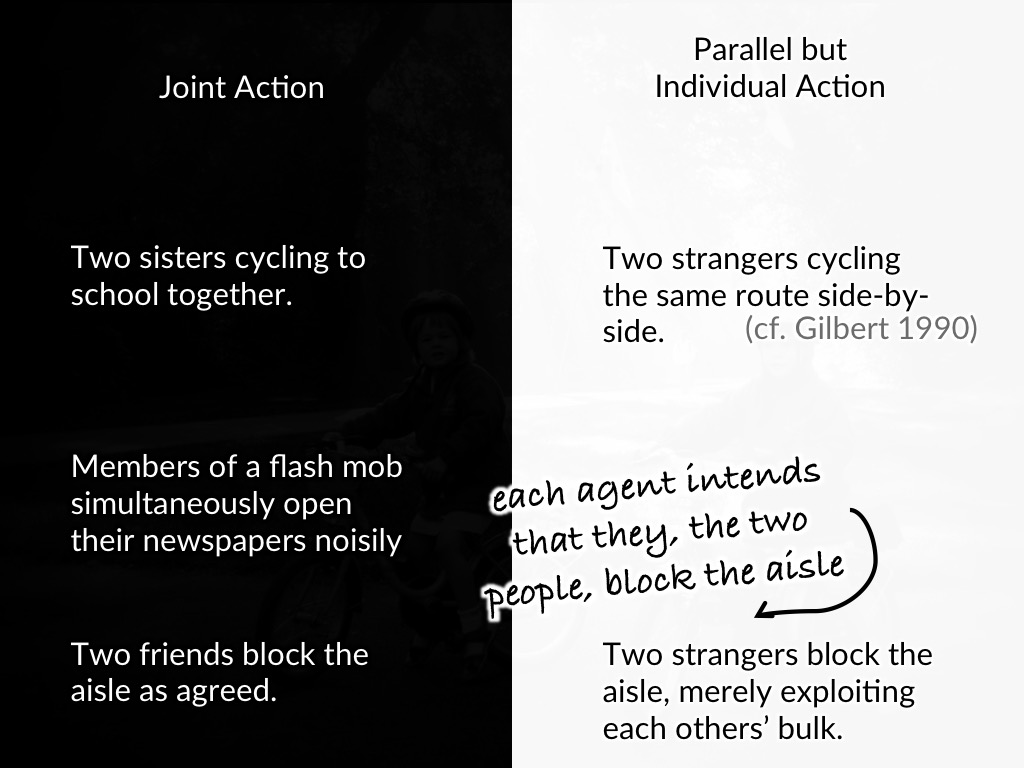

another contrast case: blocking the aisle

1. The sisters perform an intentional joint action; the strangers’ actions are parallel but merely individual.

2. In both cases, the conditions of the Simple Theory are met.

therefore:

3. The Simple Theory does not correctly answer the question, What distinguishes joint actions from parallel but merely individual actions?

Question

What distinguishes joint actions from parallel but merely individual actions?

The Simple Theory

Joint actions are actions with two or more agents ✘

Joint actions are events with two or more agents ✘

short essay question:

Why, if at all, do we need a theory of shared intention?

(Will be a while before this question makes sense.)

plan d’attaque

premise: Shared intention can only be understood as the solution to a problem.

1. What is the Problem of Joint Action? ✓

2. Can we solve the Problem without shared intention? ✓

3. If we do need shared intention, what is the best account available? ✓

Cecilia1234-dot

Question about Davidson's I chapter: Agent, Reasons and Causes, in R. Binkley, R. Bronaugh, & A. Marras (Eds.)

May we have a clearer explanation of what "primary reason" means and the relevant necessary condition stated by Davidson?

‘Giving the reason why an agent did something is often a matter of naming the pro attitude [ie. desire] (a) or the related belief (b) or both; let me call this pair the primary reason why the agent performed the action.

Now it is possible both to reformulate the claim that rationalizations are causal explanations and to give structure to the argument by stating two theses about primary reasons:’

1. In order to understand how a reason of any kind rationalizes an action it is necessary and sufficient that we see, at least in essential outline, how to construct a primary reason.

2. The primary reason for an action is its cause.

I shall argue for these points in turn.

(Davidson, 1980, p. 4)

short essay question:

Why, if at all, do we need a theory of shared intention?

(Will be a while before this question makes sense.)

plan d’attaque

premise: Shared intention can only be understood as the solution to a problem.

1. What is the Problem of Joint Action? ✓

2. Can we solve the Problem without shared intention? ✓

3. If we do need shared intention, what is the best account available? ✓