Click here and press the right key for the next slide.

(This may not work on mobile or ipad. You can try using chrome or firefox, but even that may fail. Sorry.)

also ...

Press the left key to go backwards (or swipe right)

Press n to toggle whether notes are shown (or add '?notes' to the url before the #)

Press m or double tap to slide thumbnails (menu)

Press ? at any time to show the keyboard shortcuts

Bratman on Shared Intentional Action

shared intention

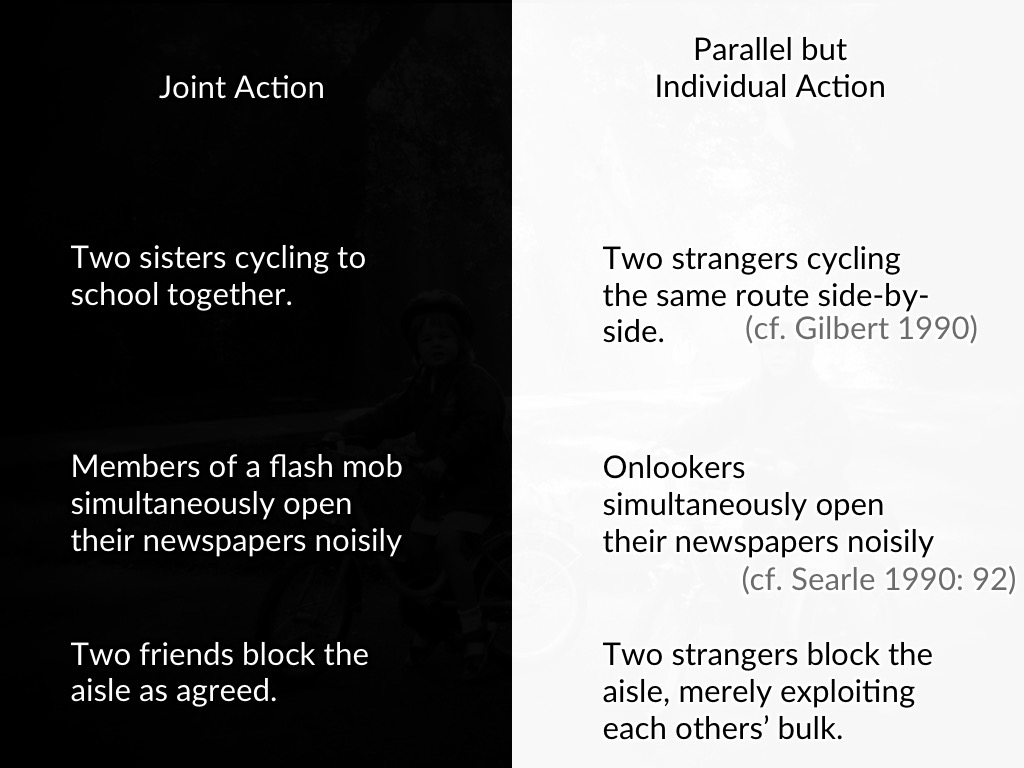

‘A first step is to say that what distinguishes’ the sisters cycling together from the strangers cycling side by side is that the sisters share an intention to cycle together ... but the strangers do not.

‘This does not, however, get us very far; for we do not yet know what a shared intention is’

Bratman, 2009 p. 152

What is shared intention?

Functional characterisation:

shared intention serves to (a) coordinate activities,

(b) coordinate planning, and

(c) structure bargaining

Constraint:

Inferential integration ... and normative integration (e.g. agglomeration)

Substantial account:

>>>

Bratman (2015, p. 32)

step 1

‘Our shared intention to paint together involves your intention that we paint and my intention that we paint.’

Bratman (2015, p. 12)

(Compare the Simple Theory)

the ‘mafia case’* motivates ... and painting the house different colours motivates ...

step 2

We each intend that we paint by way of the intentions that we paint* and by meshing* subplans of these intentions.

why??

step 3

‘there is common knowledge among the participants of the conditions cited in this construction’

Bratman (2015, p. 58)

What is shared intention?

Functional characterisation:

shared intention serves to (a) coordinate activities, (b) coordinate planning and (c) structure bargaining

Constraint:

Inferential integration... and normative integration (e.g. agglomeration)

Substantial account:

We have a shared intention that we J if

‘1. (a) I intend that we J and (b) you intend that we J

‘2. I intend that we J in accordance with and because of la, lb, and meshing subplans of la and lb; you intend [likewise] …

‘3. 1 and 2 are common knowledge between us’

(Bratman 1993: View 4)

Question

What distinguishes joint actions from parallel but merely individual actions?

Requirement

Any account of shared agency must draw a line between joint actions and parallel but merely individual actions.

Aim

Theoretical framework for psychology and formal models.

short essay question:

Why, if at all, do we need a theory of shared intention?

(Will be a while before this question makes sense.)

plan d’attaque

premise: Shared intention can only be understood as the solution to a problem.

1. What is the Problem of Joint Action? ✓

2. Can we solve the Problem without shared intention? ✓

3. If we do need shared intention, what is the best account available? ✓