Click here and press the right key for the next slide.

(This may not work on mobile or ipad. You can try using chrome or firefox, but even that may fail. Sorry.)

also ...

Press the left key to go backwards (or swipe right)

Press n to toggle whether notes are shown (or add '?notes' to the url before the #)

Press m or double tap to slide thumbnails (menu)

Press ? at any time to show the keyboard shortcuts

Introduction

compatible stories about different things?

contradictory stories about one thing?

aspects of a single larger story?

very roughly, action comprises

goal selection

(habitual vs goal-directed)

and

goal execution

(???)

essay questions related to todays lecture

How, if at all, should a philosophical theory of action incorporate scientific discoveries about the control of action?

Could some motor representations be intentions?

Which psychological structures enable agents to coordinate their plans? What if anything do these mechanisms reveal about how acting together differs from acting in parallel but merely individually?

How, if at all, should a philosophical theory of acting together incorporate scientific discoveries about the interpersonal coordination of action?

problem of action

‘The history of philosophical reflection on action gives the distinction between activity and passivity different names, and attempts to explain the distinction in different ways.

But philosophers circle the distinction repeatedly [...].

Aristotle wants to know the difference between being cut and cutting.

Hobbes wants to know the difference between vital motions, like the motion of the blood, and voluntary motion, as in bodily action.

Wittgenstein wants to know the difference between my arm going up and my raising it.’

(Shepherd, 2021, p. 1)

‘Now what is an action? Not one thing, but a series of two things: the state of mind called a volition, followed by an effect. The volition or intention to produce the effect, is one thing; the effect produced in consequence of the intention, is another thing; the two together constitute the action.’

Mill, System of Logic (1.3.6) quoted in Hyman (2015, p. 218)

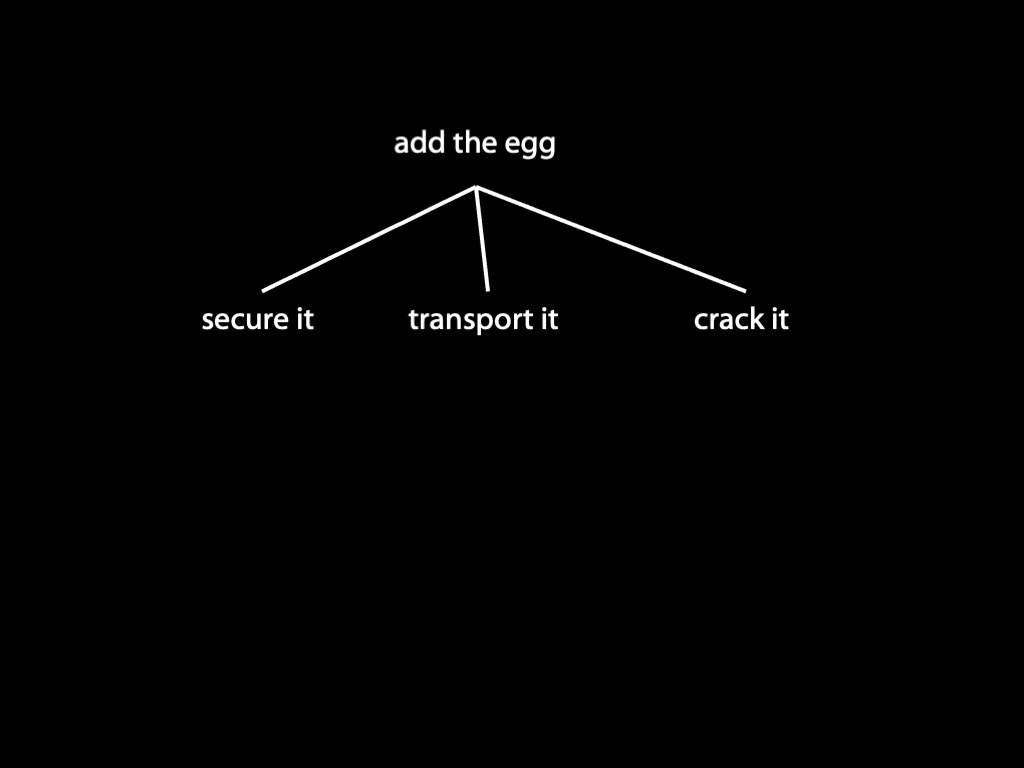

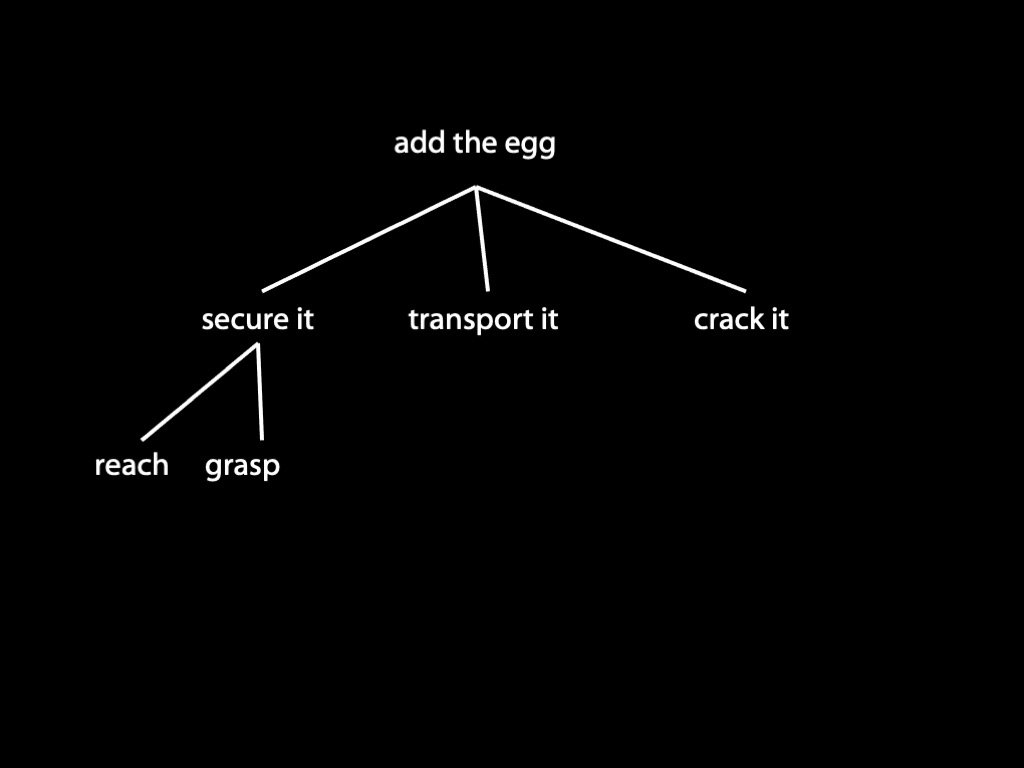

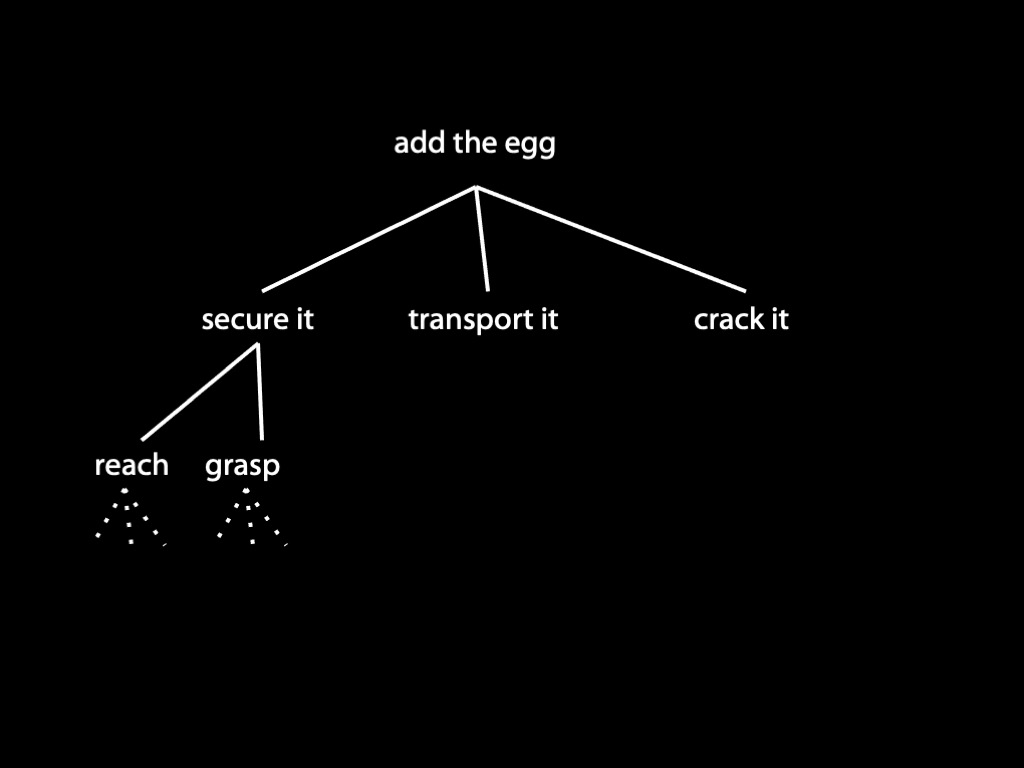

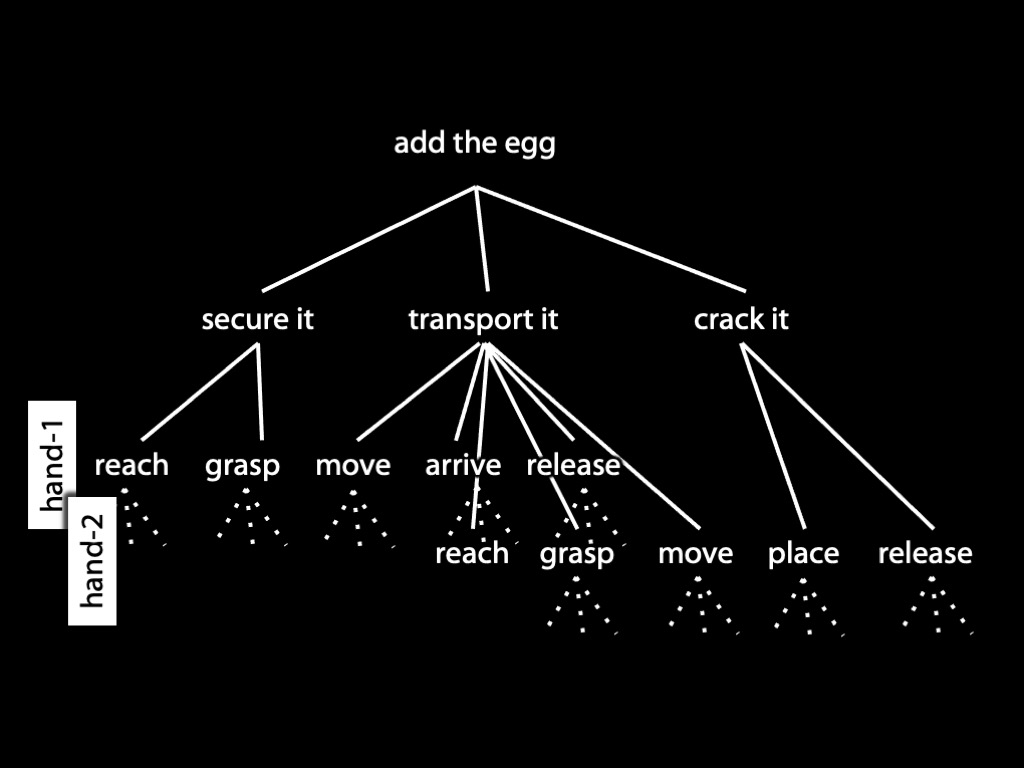

instrumental actions can have parts

which are themselves instrumental actions

Jusczyk (1997, p. 44)

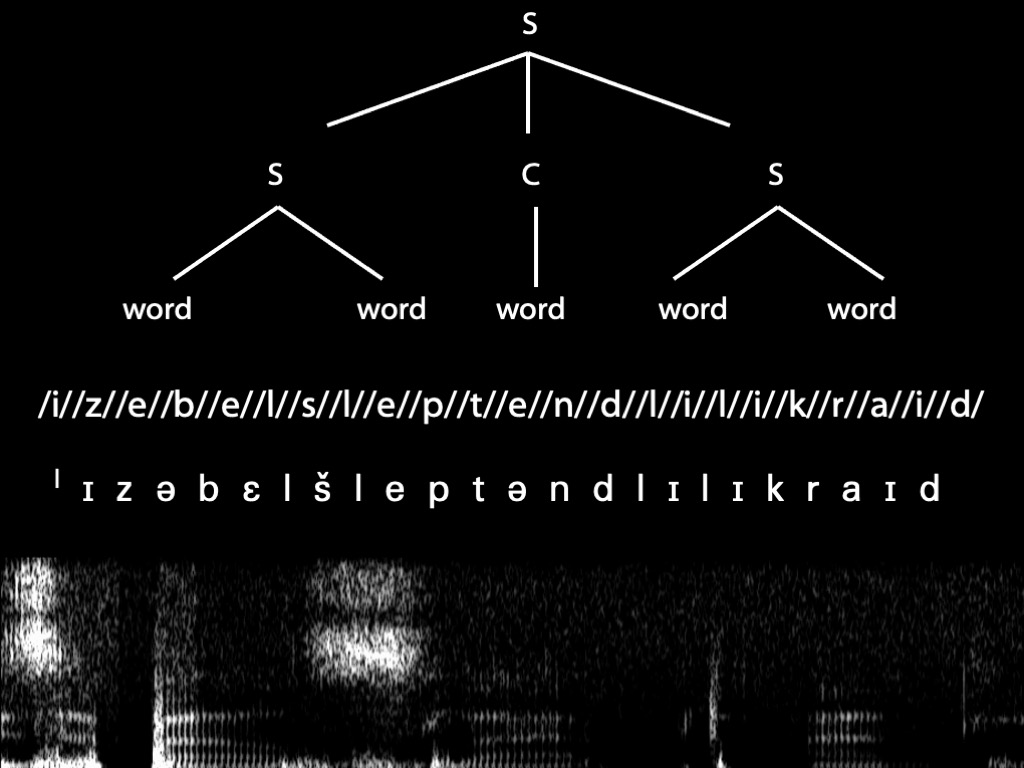

instrumental actions

Small Scale

Very Small Scale

adding the egg to the mix

grasping the egg

uttering a word

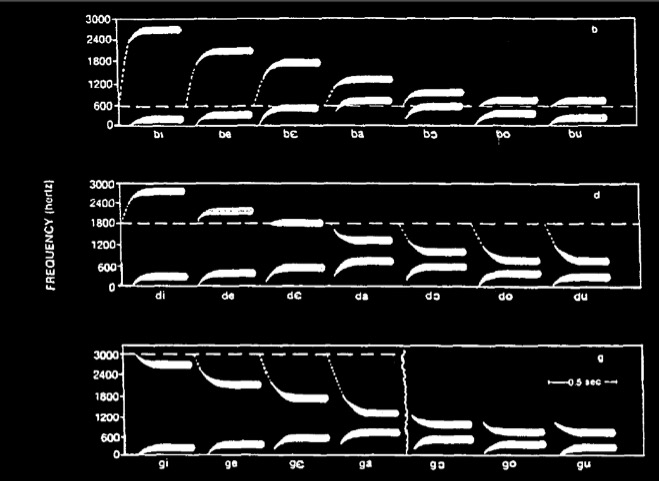

making a phonetic gesture

Why care about very small scale instrumental actions?

What is the relation between an instrumental action and the outcome or outcomes to which it is directed?

What is the relation between an instrumental action and the outcome or outcomes to which it is directed?

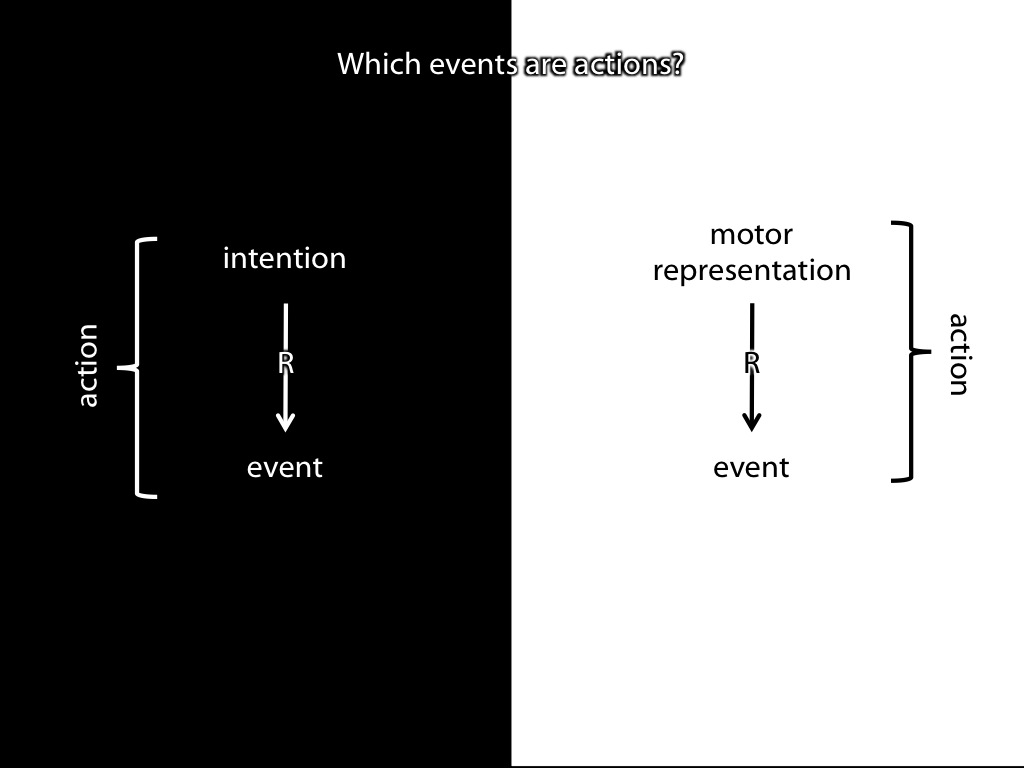

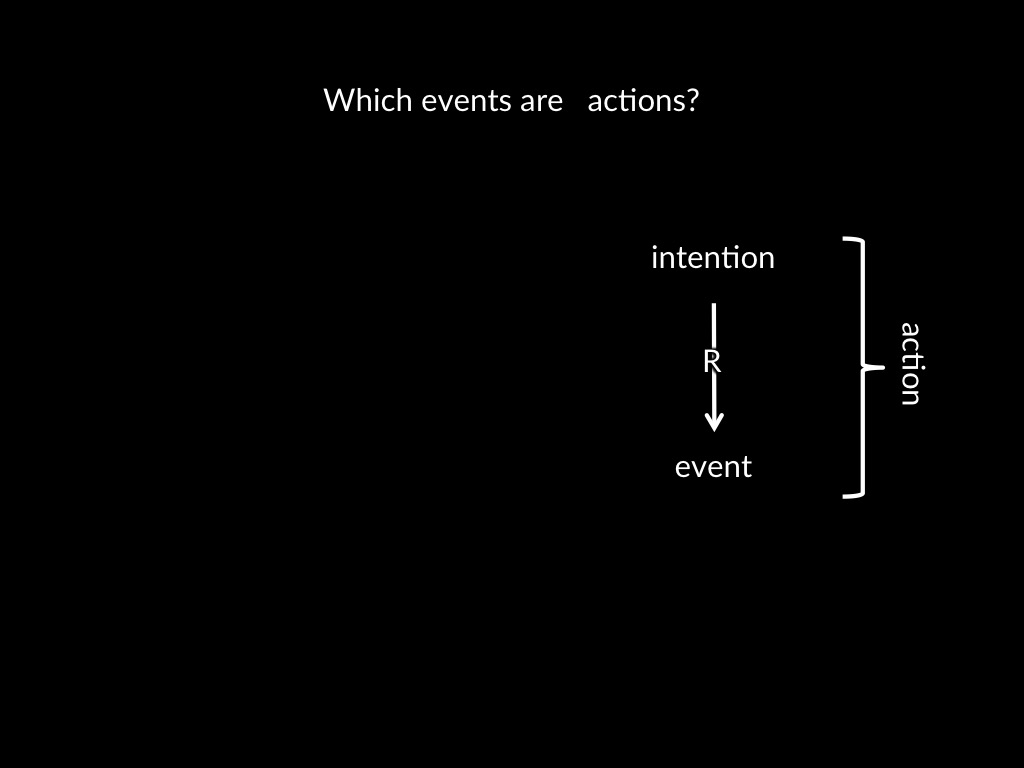

intention

The outcome is related to the action via an intention.

The intention specifies an outcome.

The intention causes the actions in a way that would normally increase the probability of the specified outcome ocurring.

<-- does not work for very small scale actions

(in general, there may be some exceptions)

(also, habitual processes will not solve this)

plan

1. What is the relation between a very small scale instrumental action and the outcome or outcomes to which it is directed?

2. How, if at all, does answering this question challenge the Standard Answer to the Problem of Action?

3. Is there a parallel set of issues concerning joint action?