Click here and press the right key for the next slide.

(This may not work on mobile or ipad. You can try using chrome or firefox, but even that may fail. Sorry.)

also ...

Press the left key to go backwards (or swipe right)

Press n to toggle whether notes are shown (or add '?notes' to the url before the #)

Press m or double tap to slide thumbnails (menu)

Press ? at any time to show the keyboard shortcuts

Introduction: Why Investigate Philosophical Issues in Behavioural Science?

challenge

Discover why people act,

individually and jointly.

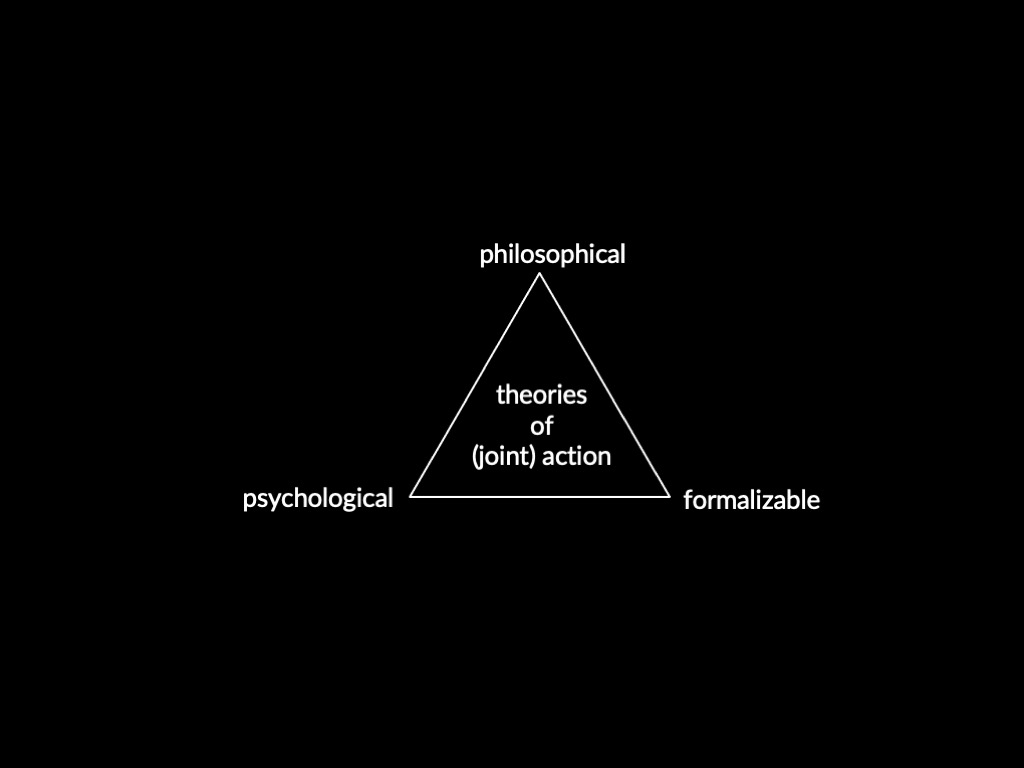

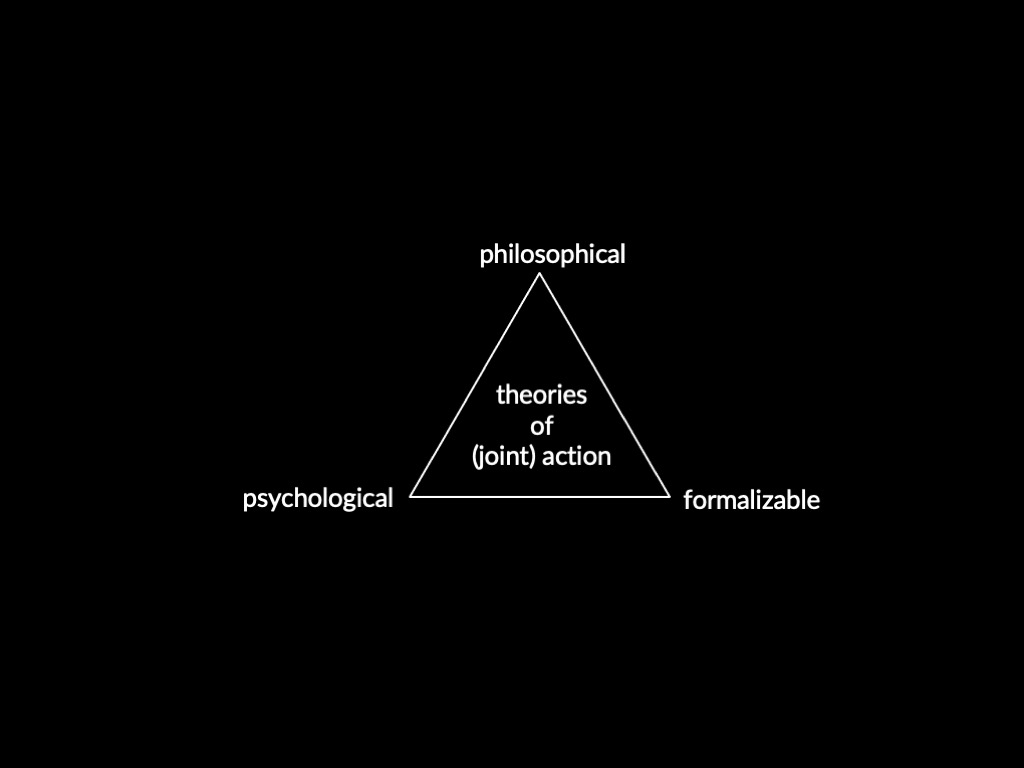

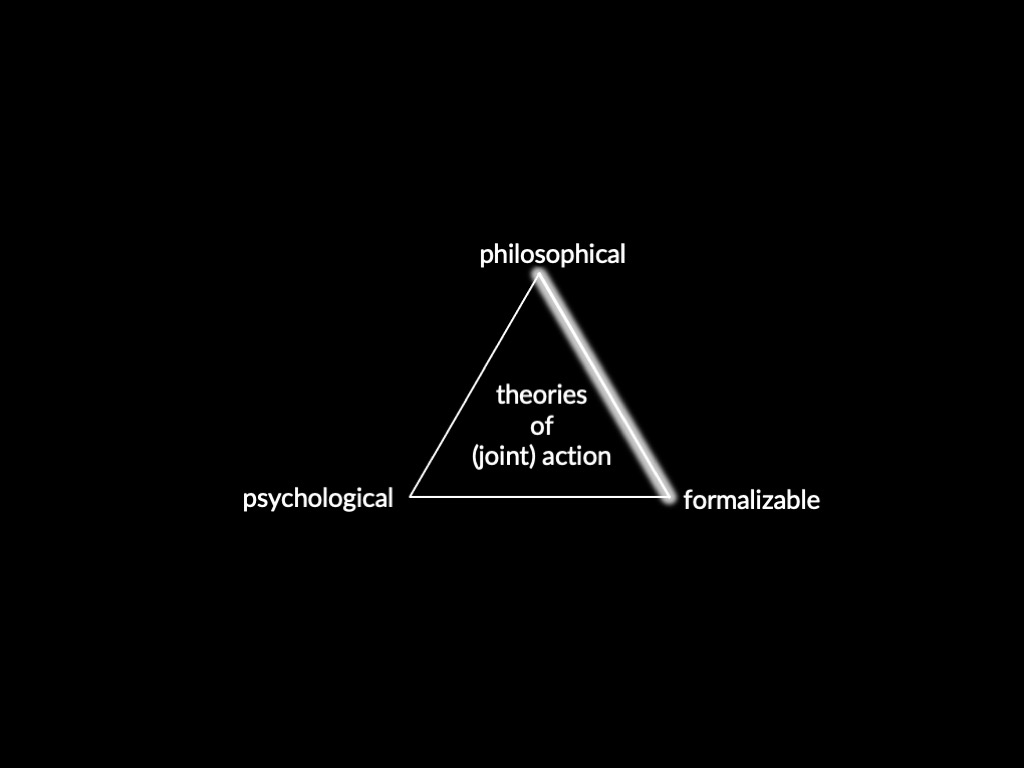

Integration Question

Why are you here?

challenge

Discover why people act,

individually and jointly.

When you act,

there are reasons why you act;

you know the reasons;

you act because you know the reasons; and

the reasons justify your action. make your action intelligible.

How can we turn this into a theory? Is it true?

three illustrations

1.

game theory

When you act,

there are reasons why you act;

you know the reasons;

you act because you know the reasons; and

the reasons justify your action. make your action intelligible.

1. Game-theoretic explanations do not involve knowledge of reasons.

2. Game-theoretic explanations do apply to some human actions.

∴

3. Not all human actions involve knowledge of reasons.

challenge

Discover why people act,

individually and jointly.

Integration Question

2.

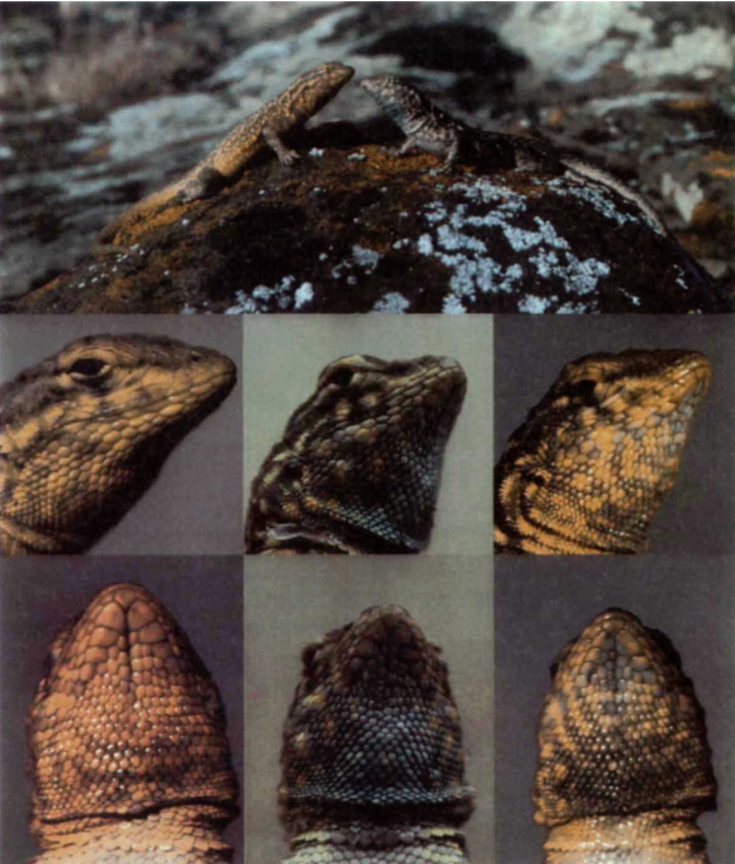

anarchic hand syndrome

When you act,

there are reasons why you act;

you know the reasons;

you act because you know the reasons; and

the reasons justify your action. make your action intelligible.

‘The right hand frequently carried out complex activities that were not willed by G.C.

(Della Sala et al., 1991, p. 1114)

challenge

Discover why people act,

individually and jointly.

Integration Question

3.

habitual processes

challenge

Discover why people act,

individually and jointly.

challenge

Discover why people act,

individually and jointly.

challenge

Discover why people act,

individually and jointly.

When you act,

there are reasons why you act;

you know the reasons;

you act because you know the reasons; and

the reasons justify your action. make your action intelligible.

How can we turn this into a theory? Is it true?

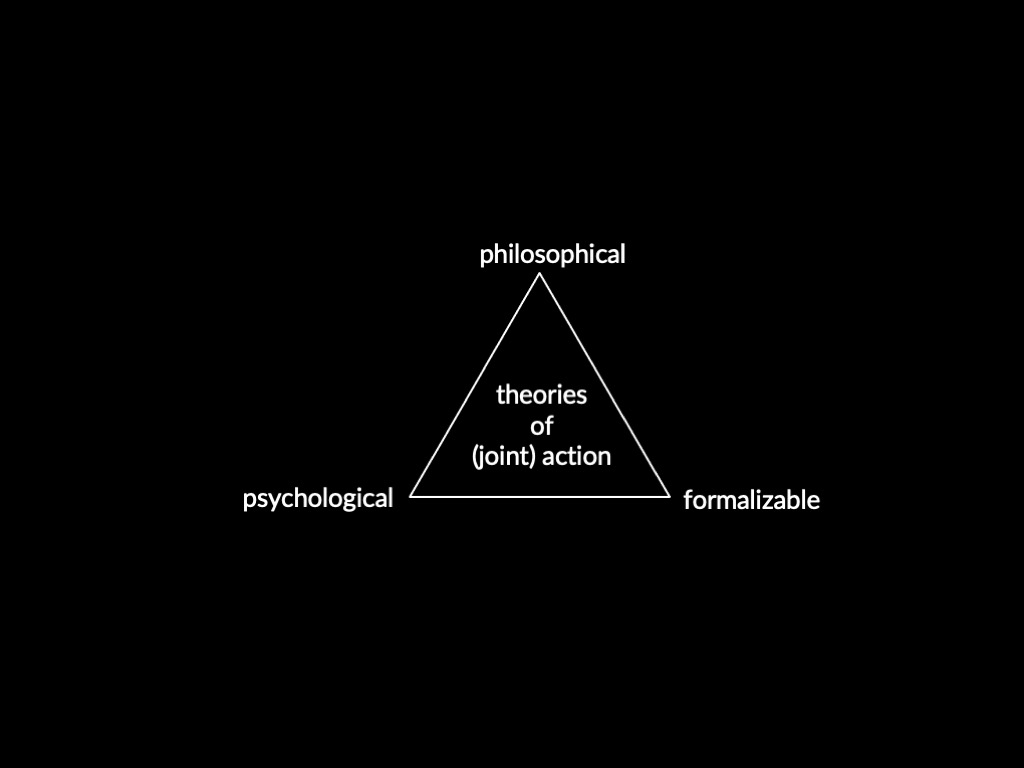

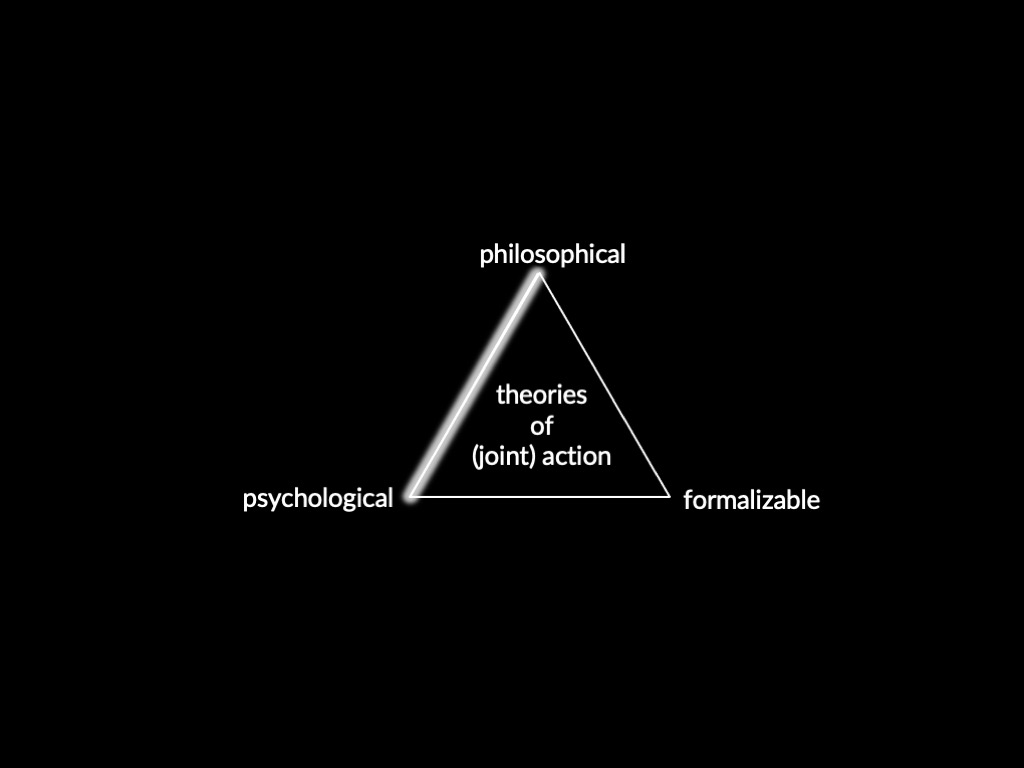

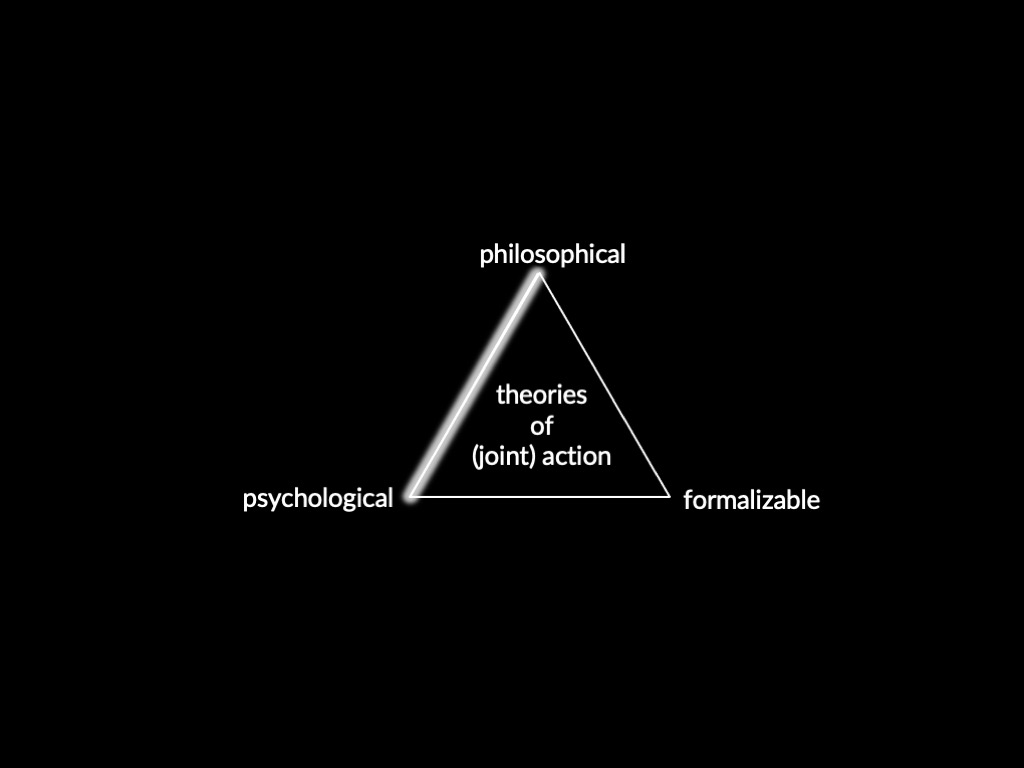

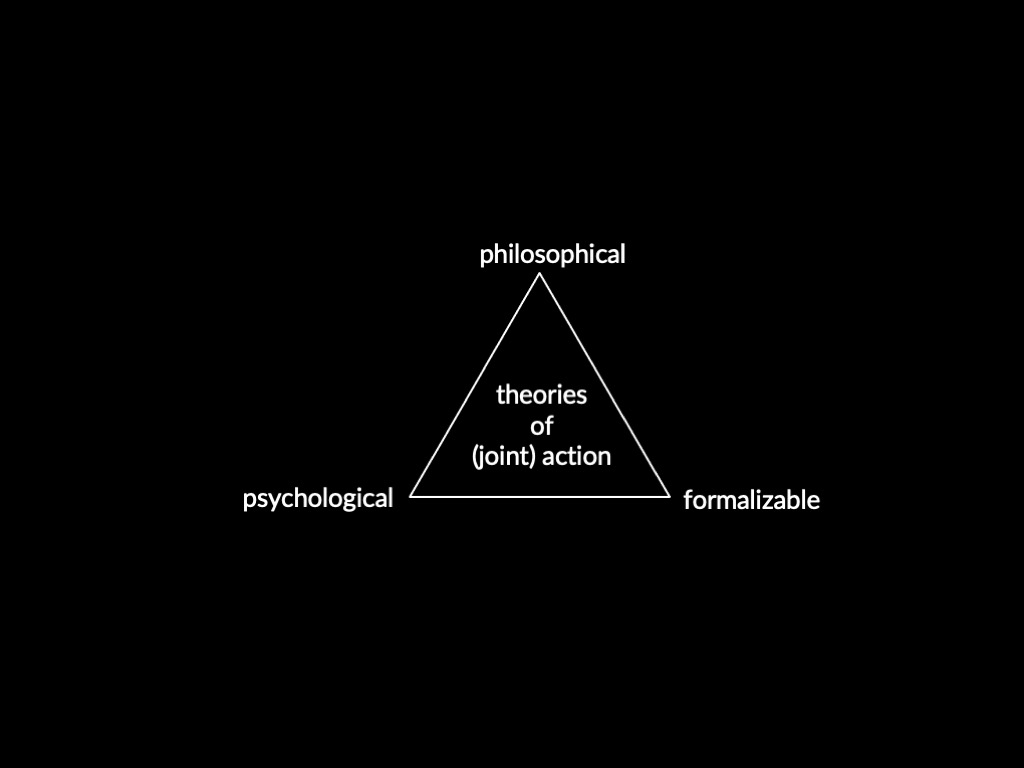

Philosophical Issues

in

Behavioural Science:

from Individual

to Collaborative

Action