Click here and press the right key for the next slide.

(This may not work on mobile or ipad. You can try using chrome or firefox, but even that may fail. Sorry.)

also ...

Press the left key to go backwards (or swipe right)

Press n to toggle whether notes are shown (or add '?notes' to the url before the #)

Press m or double tap to slide thumbnails (menu)

Press ? at any time to show the keyboard shortcuts

Could Motor Representations Ground Collective Goals?

In virtue of what could two or more agents’ actions have a collective goal?

a clue:

motor representations concerning

another’s actions occur in joint action

Kourtis, Sebanz, & Knoblich (2013)

Kourtis et al. (2013)

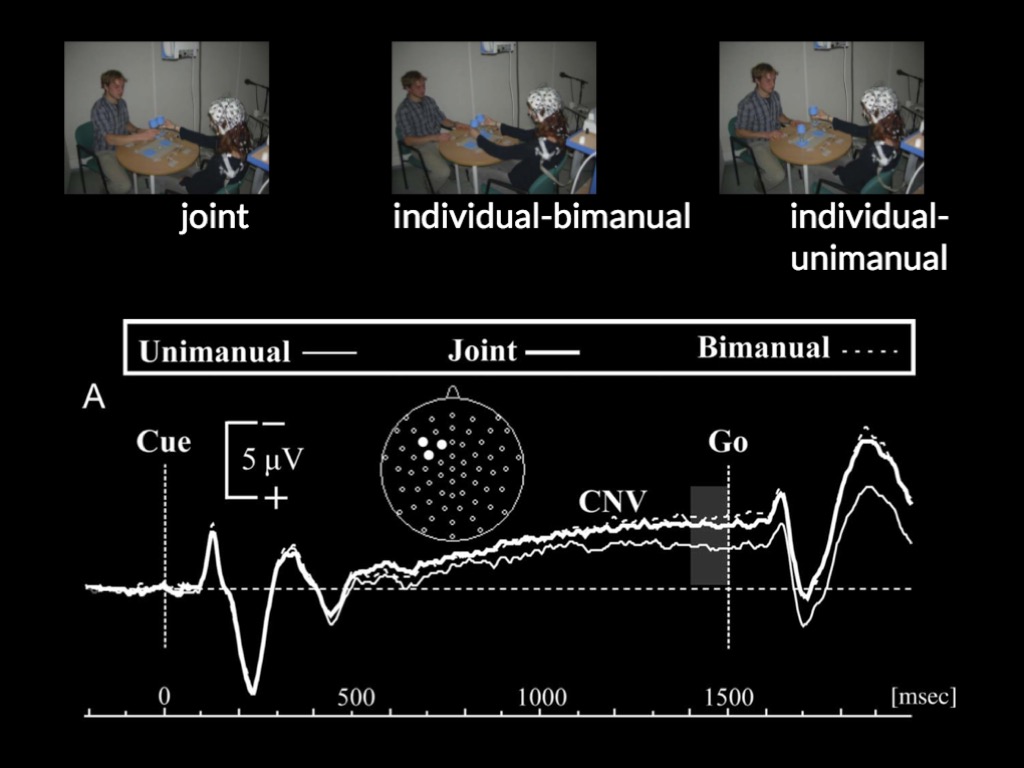

Kourtis et al. (2013, p. figure 5)

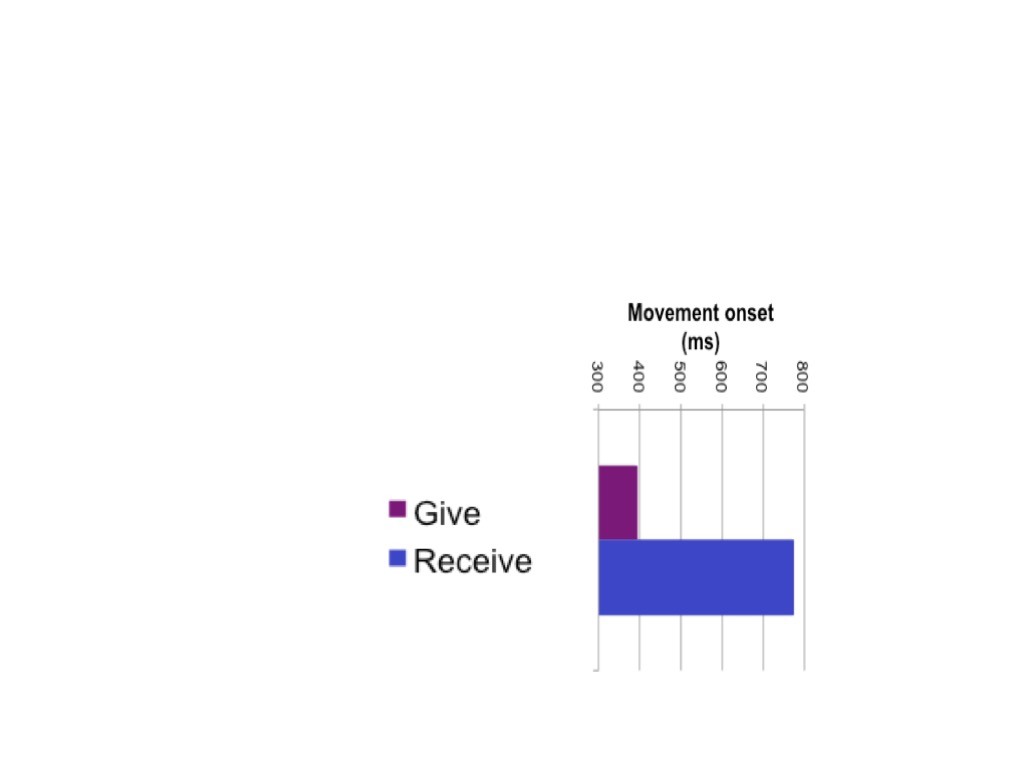

Kourtis, Knoblich, Woźniak, & Sebanz (2014, p. figure 1c)

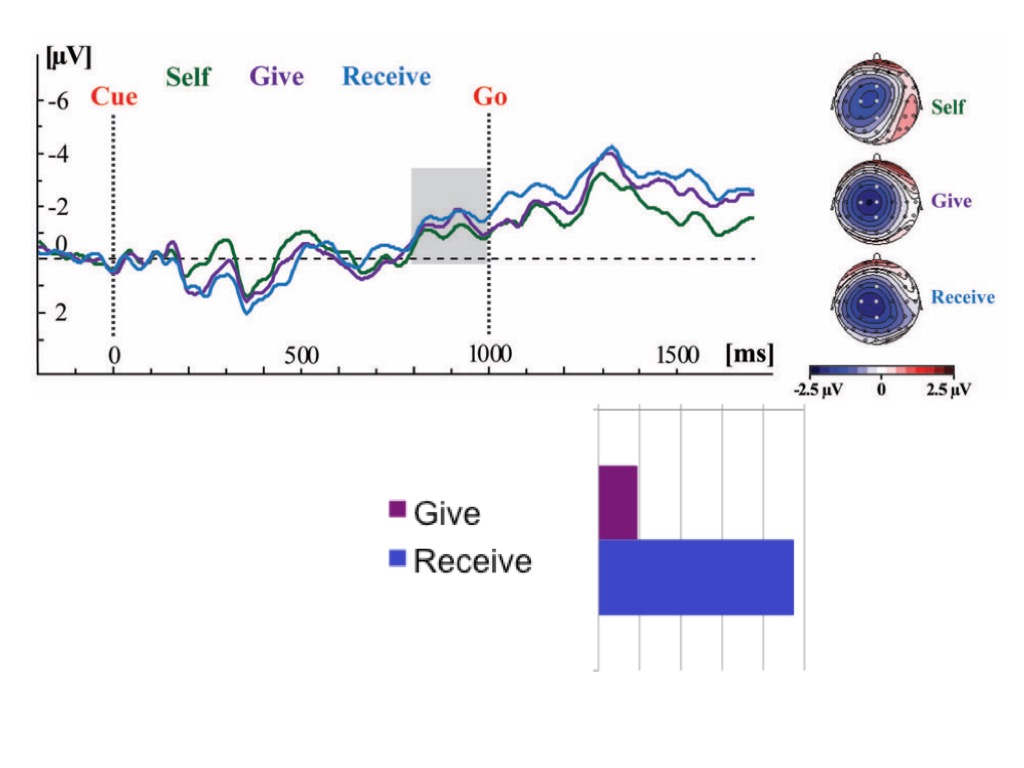

Kourtis et al. (2014, p. figure 4a)

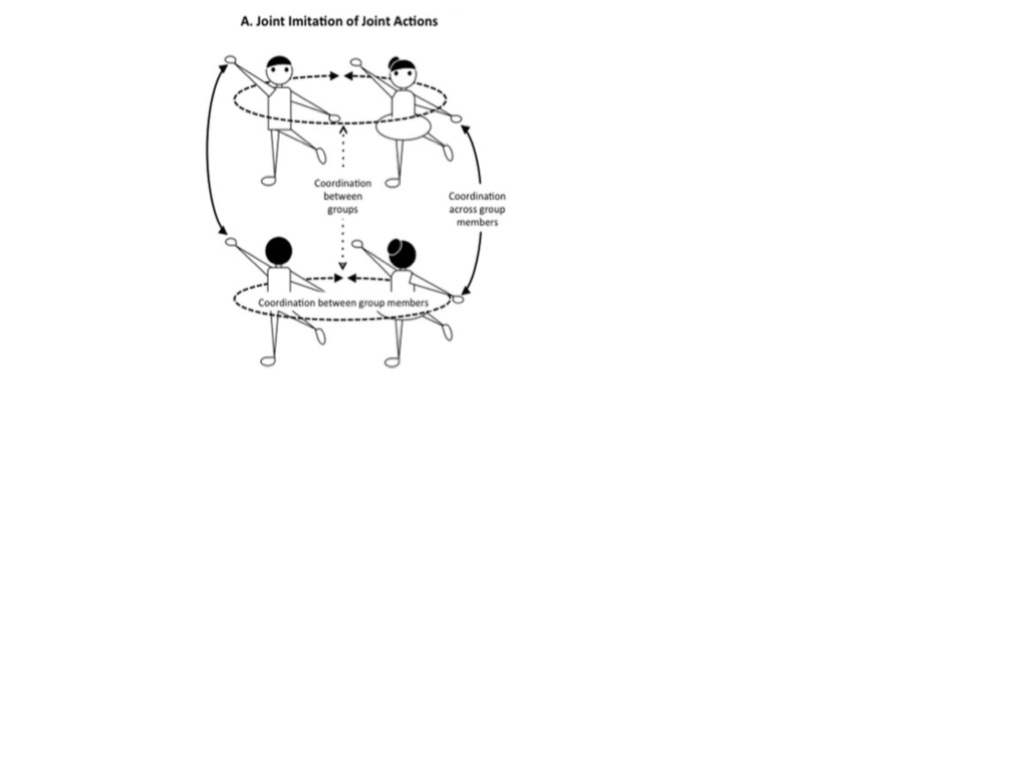

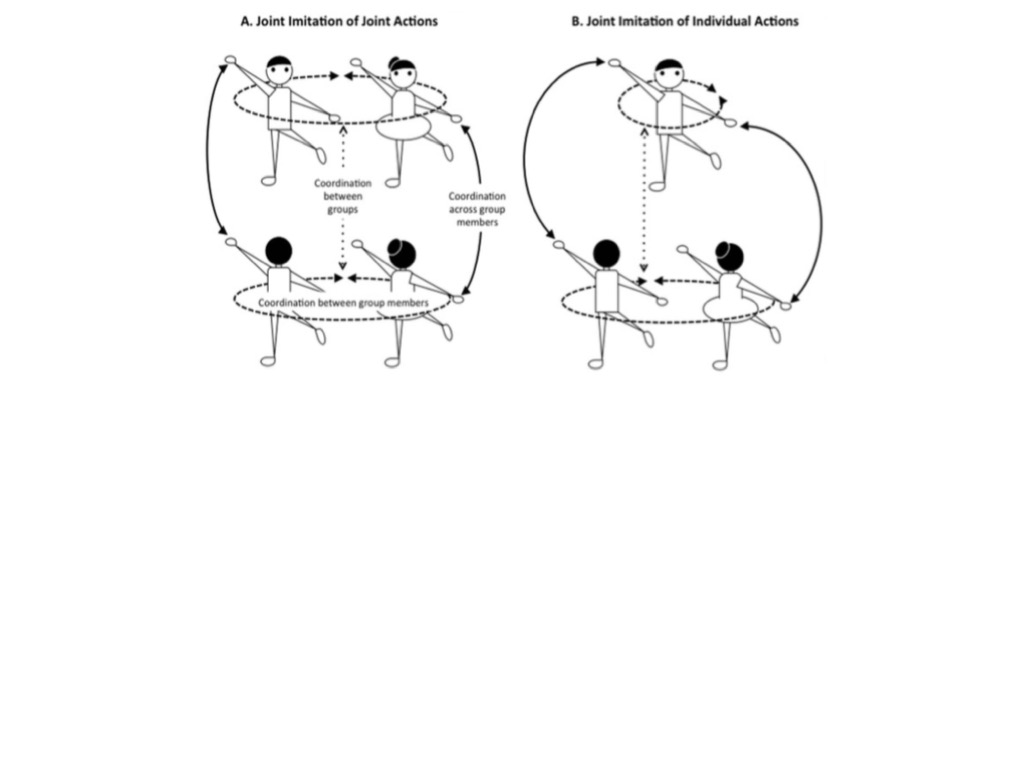

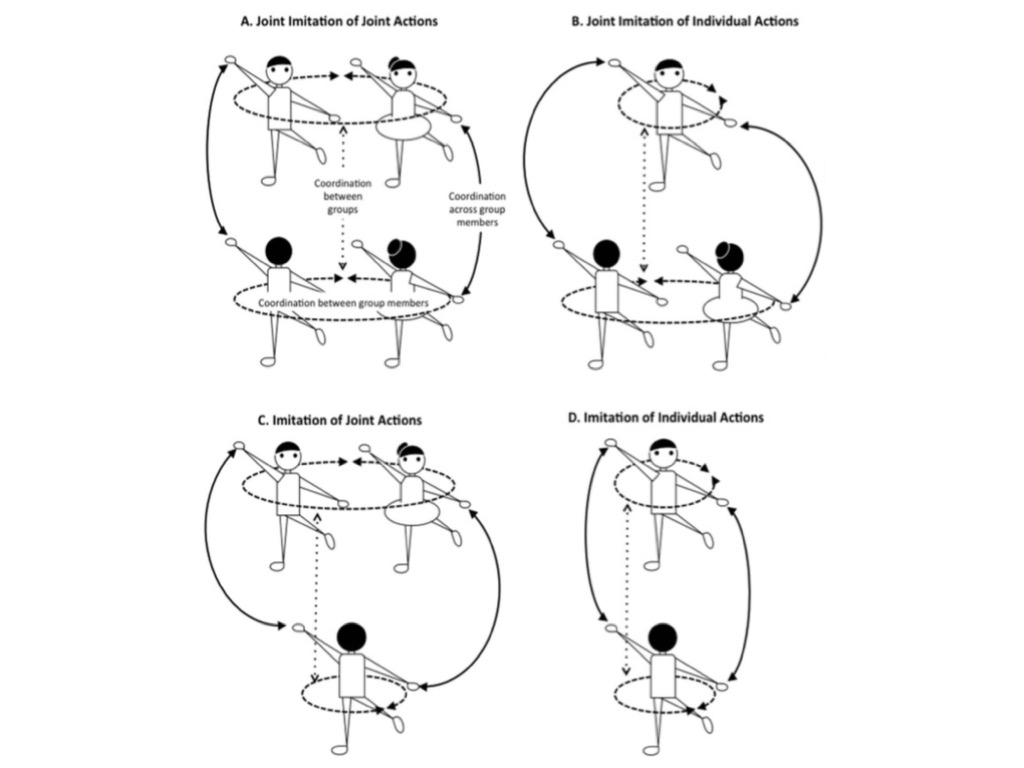

Ramenzoni et al, 2014 figure 1

Ramenzoni et al, 2014 figure 1

Ramenzoni et al, 2014 figure 1

What are those motor representations doing here?

Conjecture:

Collective goals are represented motorically.

Prediction 1 (della Gatta et al., 2017):

Framing two agents’ simultaneous unimanual actions as joint can induce effects similar to bimanual coupling.

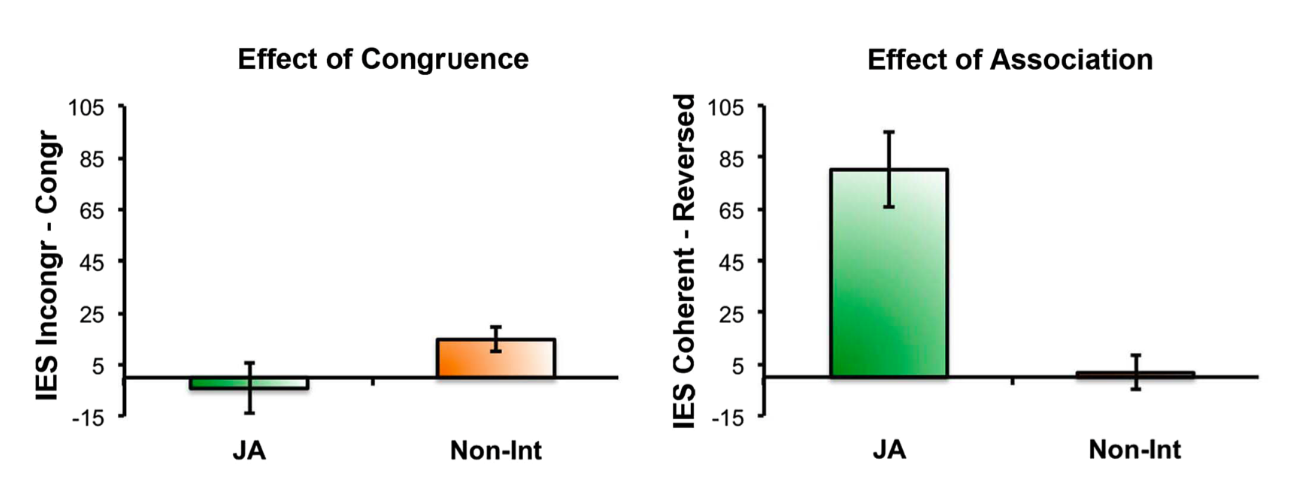

Prediction 2 (Sacheli et al., 2018):

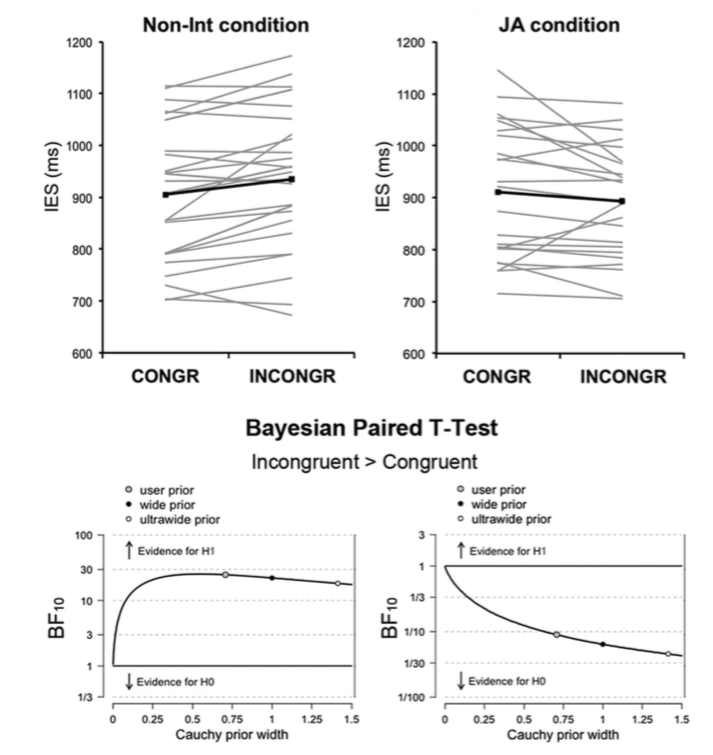

Framing two agents’ sequential actions as a joint action modulates the effects of ‘incongruent’ actions.

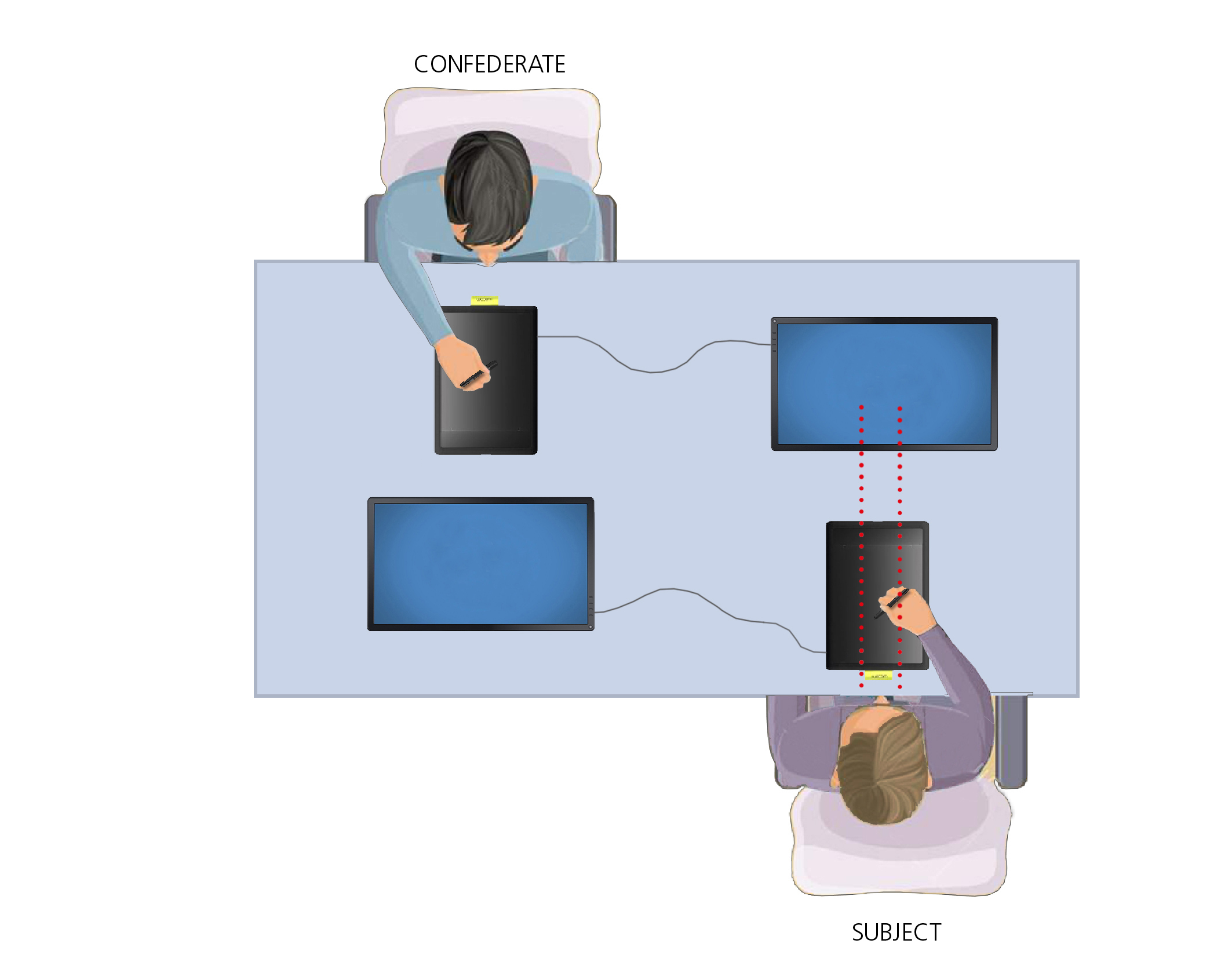

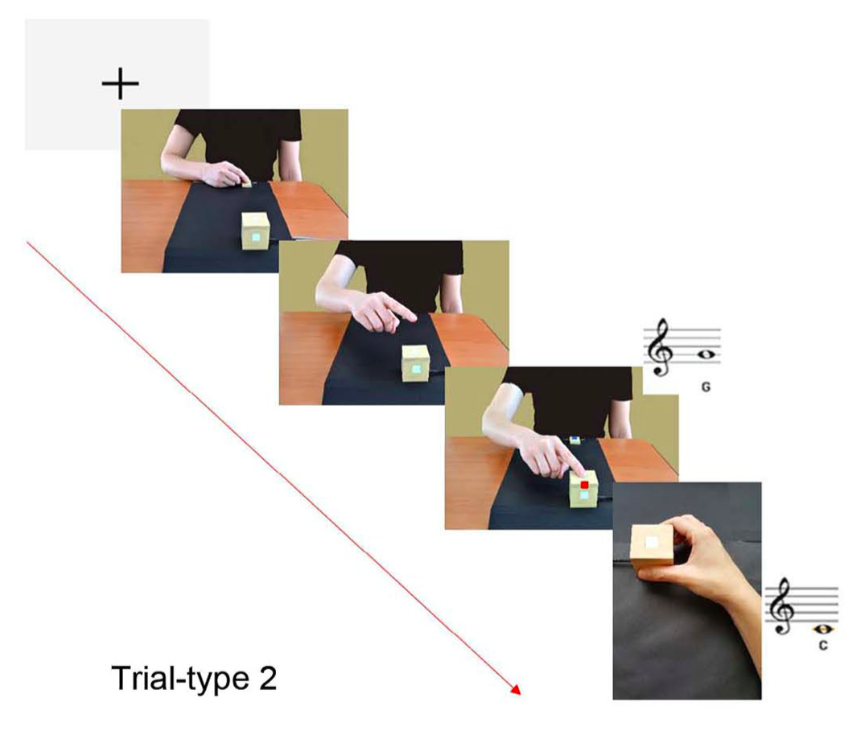

Sacheli et al, 2018 figure 2 (part)

Sacheli et al, 2018 figure 5

Sacheli et al, 2018 figure 3

Conjecture:

Collective goals are represented motorically.

Prediction 1 (della Gatta et al, 2017):

Framing two agents’ simultaneous unimanual actions as joint can induce effects similar to bimanual coupling.

Prediction 2 (Sacheli et al):

Framing two agents’ sequential actions as a joint action modulates the effects of ‘incongruent’ actions.

In virtue of what could two or more agents’ actions have a collective goal?

joint action

What is the relation between a joint action and the outcome or outcomes to which it is collectively directed?

Could motor representations also ground this relation? ✓

ordinary, individual action

What is the relation between an instrumental action and the outcome or outcomes to which it is directed?

Motor representations ground this relation.

individual action

joint action

intentions

vs motor representations of outcomes

shared intentions

vs motor representations of collective goals

Nonstandard Solutions

An action is an event that is appropriately related to a motor representation.

A joint action is an event that is appropriately related to some motor representations of a collective goal.

Objection 2 (individual)

The Problem of Action

Invoking motor representations yields a solution that is no worse than the Standard Solution.

Objection 2 (joint)

The Problem of Joint Action

Invoking motor representations of collective goals yields a solution that is no worse than one which involves invoking Shared Intention.

plan (from lecture 07)

1. What is the relation between a very small scale instrumental action and the outcome or outcomes to which it is directed? ✓

2. How, if at all, does answering this question challenge the Standard Answer to the Problem of Action? ✓

3. Is there a parallel set of issues concerning joint action? ✓

1. Solve the Problem of Action. ✓

2. Identify a role for motor representation in joint action. ✓